artthrob picks

The Dakar Biennale 2014

By Olga Speakes and Anna Stielau on 20 June

Aimé Césaire,

.

Photograph

At the Global Black Consciousness conference in the Hotel Soukhamon, Dakar, the philosopher Souleymane Bachir Diagne concluded his paper by quoting poet Aimé Césaire: 'at the end of individual singularity…' he suggested, 'at the end of difference, is the community of all.' It goes without saying that Césaire’s ghost – and the spirit of his long-time student and friend, former Senegalese president Léopold Sédar Senghor – stalked the fringes of the conference proceedings. Contemporary Black Consciousness thought is heavily indebted to both thinkers, after all. In this particular instance, however, Diagne was engineering a conversation between Césaire and the theme of this year’s Dak’Art biennale, ‘Producing the Common’.

art events calendar

VIEW FULL CALENDARbuy art prints

edition of 60: R7,000.00

About Editions for ArtThrob

Outstanding prints by top South African artists. Your chance to purchase SA art at affordable prices.

FIND OUT MORE Editions for artthrobIt doesn’t take a lot of work to locate Césaire in Dak’Art. He’s been there before. Now in its 11th iteration, the biennale is an ideological successor to Senghor’s Premier Festival Mondial des Artes Negre (or First Festival of Negro Arts), at which the poet was a guest speaker. Re-envisioned in 1989 as a cultural festival, Dak’Art has evolved into the most established and comprehensive exhibition of its kind on the African continent. 2014 saw the inclusion of 62 artists on the main international exhibition, and a further 250 in the accompanying fringe festival, known as the ‘OFF’. As a cultural phenomenon, the event has come a long way since Césaire addressed his audience in the city. It nonetheless retains a strong socio-political undercurrent.

‘Producing the Common’, as imagined by the 2014 curatorial team – Elise Atangana, Smooth Ugochukwu Nzweni and Abdelkader Damani – is rooted in the connection between aesthetics and politics. Taking inspiration from Senghor’s Negritude movement and drawing extensively on Jacques Ranciere’s writings on collectivity, the Biennale was set to focus on the transformative power of art and artistic process as a public vocation. The main exhibitions of the Biennale had a distinctly cosmopolitan feel that would not seem out of place in any of the numerous mega-exhibitions taking place around the globe (complete with converted industrial warehouse type spaces, international curatorial team and sleek if not always perfectly executed design). Looking to unsettle the hierarchical divisions between different types of knowledge and aesthetic production, these central events entered into a dialogue with the OFF programme. The OFF events varied hugely in scale, quality and impact – from the aforementioned Black Consciousness conference to open studios of local artists and designers in remote suburbs and exhibits in hotel lobbies and restaurants. Although, at times, hard to navigate (and to locate) the OFF programme managed to catch the popular, communal spirit of the event. As emphasised in the curatorial statement, this dynamic has been envisaged as the project of both the government and the people of Senegal from the exhibition’s inception.

Dak'Art Conference

2014

Photograph

It seemed that the curators were determined to experiment with – and to combine different curatorial strategies within – this year’s edition of Dak’Art. Rather than favouring either approach, their choices suggested that contemporary art from Africa or from anywhere in the world could be showcased on the continent using platforms, formats and means of production that are available to cultural producers anywhere. Finding one’s own voice and adapting a universalised curatorial language to the local context (not just the African context in general but the context of the specific country and city) where such an event takes place, becomes a crucial point of success or failure. It is both a curatorial challenge and an opportunity.

As a standpoint on shared experience and creative practice, ‘Producing the Common’ can be seen in a new light when read in conjunction with the emphatic manifesto published as a centrefold in the first print edition of Berlin-based art website Contemporary And. Entitled ‘Senegalese art collectors beware!’ the text was produced by an anonymous (and evidently very agitated) collective that goes by the Orwellian nom de plume Le Bureau de Vigilante des Questionnements non resolus, or ‘The Vigilante Office of Unresolved Questions’. It deserves to be quoted at length:

'In Senegal, at least three or four collectors have the ambition of creating a museum. These aims are welcomed and encouraged, even if they are taking a long time to materialise. The URGENCY (or state of emergency) that we face today, is for this small group of collectors (including those we hope will dare to emerge soon) to have the magnanimity to be heard and to DO SOMETHING CONCRETE NOW. Because if Senegalese collectors do not come out and demonstrate evidence of their acquisitions, the heritage of post-independence Senegal WILL LEAVE THE SHORES OF THIS COUNTRY only to reappear in certain major museums of contemporary art, whose current search spans the globe. Today, these museums take on the missions of earlier ethnographic institutions and buy new, as yet unknown art production from all over the world

The meaning or final purpose of this MANIFESTO is to set in motion a flow exchange between Senegalese art collectors themselves. And subsequently artists, audiences, private and state institutions. In short, it is about a process that takes on different forms and can have positive repercussions on national (and African) culture, and subsequently on Senegalese society.' (emphasis author’s own).

There are some interesting observations made in those two, vaguely militant paragraphs alone, and they warrant interrogation in the context of Dak’Art. First, the notion of a larger ‘African culture’ that extends beyond rigid national borders; a construction that recalls Césaire’s call for a community at the end of (in this case, national) difference. Second, the invisibility of a concrete Senegalese art market, leading to local art practitioners seeking their fortune in the West and taking their wares with them. And thirdly, the neo-ethnographic project of international art institutions, many of whom were well-represented at the Dak’Art 2014 opening event.

Let’s think about this in terms of another concept introduced by Edouard Glissant, a Martinican writer and critic closely associated with the Negritude movement. His idea of ‘Whole-World’ (Tout-Monde) was also central to this year’s Biennale and its change of emphasis. In acknowledgement of this ideal, 2014 saw the biennale opened up to artists from outside of Africa. This inclusion marks an effort to engage with the idea of art as an agent of change not just on the continent but globally, in an attempt to increase the international profile of Dak’Art in a wider world – and through the exhibition, the art represented within it. Moving away from ‘an African ghetto’, in the words of the newly appointed Dak’Art Secretary-General, Babacar Mbaye Diop, was an important step in claiming internationalism.

Putting aside the dubious connotations of isolation and cultural impoverishment implicit in the phrase ‘African ghetto’ for now, how does Dak’Art embrace internationalism, and at what cost? In an effort to foster dialogue within a broader global community the Biennale was opened to non-African nationals in the form of an invited artists exhibition titled 'Cultural Diversity' and staged at the IFAN Theodore Monod Museum. In the same spirit – it could be termed unity through diversity, perhaps – artworks by North African, sub-Saharan and diasporic artists were displayed side by side in the open spaces of the exhibition venue (although they had been divided geographically among the three curators during the selection process). Rather than homogenise the experiences of artists from different national backgrounds, 'Producing the Common' provided a nexus around which to locate diverse practitioners as equal contributors to a global art community. Opening up a rich dialogue between the different players, this strategy was ostensibly an attempt to re-invigorate Leopold Senghor’s vision of reclaiming African cultural production.

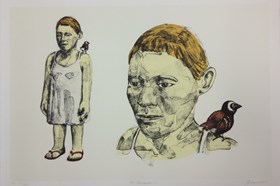

Nomusa Makhubu

Goduka (Going/ Migrant Labourers)

2013

Digital print on archival Litho paper

60 x 80 cm

The idea of ‘Whole-Worldness’ was also made manifest in the exhibition 'Anonymous' that accompanied the main show in the central Village de la Biennale. As an opportunity to make explicit Ranciere’s theories about the power of equality in unsettling accepted social categories, ‘Anonymous’ presented a cabinet of curiosities of sorts. Each participating artists was asked to contribute a small scale work, exhibited untitled and unsigned. This small exhibition contained a reference to the not-so-distant past, when much African cultured production was rendered anonymous – nameless, authorless, extracted from its social and historical context – by colonial politics and a Western art establishment. There’s a cheeky comment here, too, on the big name/blockbuster show politics of the art world today. In a show so populated with African art world celebrities, though – and so deeply in the shadow of those predatory neo-ethnographic EuroAmerican art museums – this strategy could be read as a symbolic gesture rather than a radical critique, as in most cases it was so easy to guess the authorship of the works.

To be fair, Dak’Art 2014 was not without altruistic intent. As highlighted in the manifesto, there has been much conversation about the creation (or recreation, as its ancestor has long crumbled into ruin) of a Senegalese Contemporary Art Museum in Dakar. Many public figures including the Minister of Arts and Culture used their public addresses during Dak’Art as a platform to call for this cultural investment, conceived of as the state of Senegal’s historical responsibility. Credit where credit is due there. Considering the challenges faced by the Biennale – the lack of a market for contemporary art on the continent, for example – Secretary General Diop’s vision for sourcing financial support for the Biennale in Africa and moving away from relying upon ‘supportive logic from Western donors’ also deserves a nod.

Dak’Art is a far cry from some of its older and more established siblings like Venice, dubbed by critics the 'Olympics of the Art World'. There is not much emphasis placed on country participation despite the presence of two pavilions representing Morocco and Algeria (and the attendance of high-profile government officials at opening ceremonies). South Africa, although without a pavilion, was well represented. Among the 62 artists invited to participate in the main international exhibition were Kira Kemper, Candice Breitz and Nomusa Makhubu. Makhubu’s contribution, Self Portrait Project, secured her the Prize Studio Nacional des Arts Contemporains, Le Fresnoy. By inserting images of herself into ethnographic-style portraits documenting colonial subjects, she succeeds in evoking in the viewer an almost physical sensation of being personally implicated in the images on display. The sense of objective distance that these archival photographs carry is obliterated. The body of the artist becomes the site for a merging of history and the present in the context of post-Apartheid South Africa. In a way, Makhubu’s work reads as a metaphor for Dak’Art itself: a palimpsest in which past and present meet.

As a site for the reimagining of contemporary African art practice, Dak’Art is uniquely equipped to speak not just on behalf of the continent, but TO the continent. In that respect, ‘Producing the Common’ may seem a little non-committal. While the end of difference and unequal relationships is a worthy cause, there are very real concerns – as outlined in the manifesto – in Senegal and on the continent at large. The questions raised by the curators about the direction in which African art production may move, about its place in the world, are not insubstantial. Negotiating the position of Dak’Art as neither a regurgitation of a Western biennale model nor parochial and insular is a challenging undertaking. Perhaps, rather than demonstrating a lack of commitment, the 11th edition of Dak’Art is another platform – another voice – in the ongoing conversation about African art both within and outside the continent. Professor Diagne might have been better off quoting an older Césaire speaking in Dakar in 1966. African art, Cesaire claims, lives in the space between individual man and society: 'That is why we cannot separate the problem of the fate of African art from the fate of the African man; that is to say, the fate of Africa itself.'