Goodman Gallery, Cape Town

05.03.2015 – 11.04.2015

The main room of the Goodman Gallery in Woodstock is an ideal setting for the panoramic grid of Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin’s Divine Violence. The noise-less, air-conditioned and unobtrusively-lit environment enhances the success of an exhibition that relies on the juxtaposition of Divine Violence‘s benignant appearance and its ‘Sturm und Drang’ message. This disjuncture creates a paradoxical space, which presents viewers with a fascinating and ironically detached surveillance of violence and power.

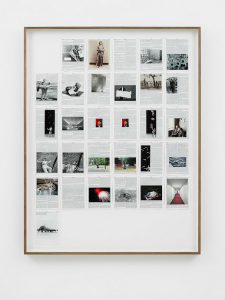

Tissue-like Bible pages, pinned with the precision and order of an entomologist’s draw, are neatly overlayed with 512 photographs from the Archive of Modern Conflict. Like impaled insects these specimens appear static and primarily informative despite their confrontational and tempestuous content. The exhibition presents the atmosphere of a museum-esque neutrality.

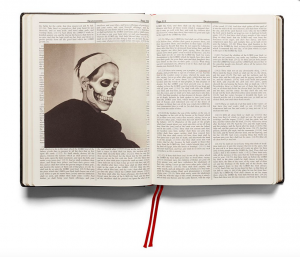

The work and the exhibition as a whole is an adaptation of Broomberg and Chanarin’s artist’s book Holy Bible (2013). Inspired by German playwright Bertolt Brecht’s customized and annotated personal bible, their version matches biblical texts with images. Having mined the Bible for instances of God’s violence, Broomberg and Chanarin draw together examples of both violence in the ancient text and modern images of violence. And it is from this catalogue of catastrophes that the spreads from Divine Violence are taken.

The exhibition and book also draw substantially on contemporary philosopher Adi Ophir’s reading of the biblical text as the Machiavellian machinations of an angry despot. The thread of power exerted through violence, and violence as an expression of power is eerily present in both ancient and contemporary times. One such work, titled Haggai, comprises a single sheet of the King James Bible on which the words “shake the heavens and earth” are neatly underscored in red. Another, Genesis, is a grid of thirty pages, among the images pasted onto them is a limp body being prodded, a sepia photograph of a native American, and a man hanged from a tree – images that capture different manifestations of violence.

Adam Broomberg & Oliver Chanarin, Genesis, 2013. King James Bible, Hahnemühle print, brass pins, Framed: 145 x 112 x 5 cm. Edition of 3

The exhibition examines a broad scope of violence in society some of which is more subtle than simple brute force. Among the images that feature in their perusal of atrocities are a portrait of a grinning black beauty-queen in America, a toilet bowl splashed with sick, and a magician spiriting a levitating showgirl.

Broomberg and Chanarin seem not to be taking a cheaply contentious shot at a religious theme so much as extrapolating on the alarming blood-lust in human nature. Their exhibition offers itself most readily for an anthropological interpretation, alleging a world where God is made in man’s image and not the other way around.