Lady Skollie, a.k.a. Laura Windvogel, is doing much more than painting pawpaws and dicks. She is on a mission to rework the South African art world from the inside, to have her voice heard, to peel back the layers of social perception (perhaps, like peeling banana skin) to get at its political and historical meat. We sat down to talk to the art and activist polymath about identity, erotics, and running the world.

KEELY SHINNERS: Why choose the name Lady Skollie? Is there a type of performativity that comes with being an artist?

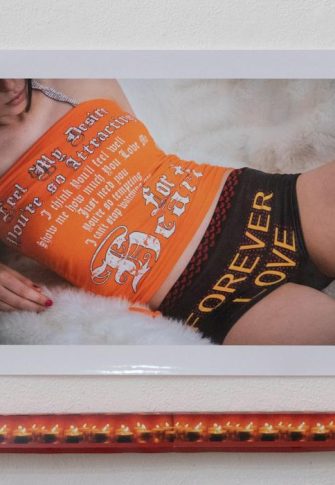

LADY SKOLLIE: Lady Skollie, for me, has always been a lesson in identity. I’ve always had these disparate elements of my personality. A couple of years ago, I had these ringlets and cute 1950s dresses. But inside, I always had this element of the obscene: wanting to be against authority, to challenge the norm. I looked like a little lady, but my mouth would be dirty. I would talk about sex and paint little dicks on people’s things. Lady Skollie was a performative thing, you’re right. The space where those two things were harmonious. It’s quite volatile in my body and mind, the ways I perceive masculinity and femininity. So Lady Skollie was a character where those elements coincided.

KS: Now that you’ve been Lady Skollie for a while, do you feel like it’s an empowering thing to have a character that you latch onto? Or do you feel it can be fragmenting?

LS: I think a bit of both. I love consistency. In the beginning, when I started being known as Lady Skollie, big galleries saw it as a “trendy” approach. Now, people ask me, “Do you still want to be listed as Lady Skollie or Laura Windvogel?” And I’m like, “Lady Skollie, obviously.” They have this thing in their minds, “How long will she be able to keep the character, keep the thing alive?” For me, it is about always tapping into either/or: the Lady bit or the Skollie bit. It releases me more. It gives me freedom in certain ways that Laura Windvogel wouldn’t.

KS: Your work deals with questions of erotics—how you relate to your body, how others relate to your body—but they’re not just about sex. Do you feel erotics can be a means of asking broader questions about politics, selfhood, relationships?

KS: You can look at bananas and pawpaws and say, ‘Oh, cute, it looks like a dick or a vagina.’ But you get into the history of those fruits as symbols of exploitation and colonization, consumption, and exotification.

LS: People want the easy thing to consume. Now, I’m in the stage where I’m actually really explaining to people what I’m trying to say. (People forget that I write. I’m like, ‘Yes, I went to university too, guys. Don’t just do dicks.’) Before, I made a lot of assumptions about my audience and my work. I wasn’t giving people the opportunity to vouch for what I do.

KS: Your work seems more explicitly personal than other visual artists. You’re also a part of this strange phenomenon of the artist’s personal life being able to be seen on Instagram, out in the open.

LS: It was a very conscious decision for my presence to be like that. I have a history of retail. It was downright bullshit, but it made me realise that everything is retail. When I worked in a gallery, artists would be there for opening night and never be there again. They would uphold this romantic notion of themselves being tortured, away in their space, and then they would complain that no one is buying their art. But if you’re not there to convince people about your work, in your own voice, they can only take what they see. Especially in South Africa. I don’t know why we have this Eurocentric way of perceiving art when it’s not the same. People here don’t have the expendable income to drop G’s on something that’s going to sit in their lounge. If someone’s going to invest a lot of money into your work, you have to let them know who you are. That was important for me. I wanted to be attainable, in a way, so that my work was attainable. I do lay-buys, which ties into my commentary on coloured culture.

I worked in galleries. I know how the system works. I did the books for a gallery, guys. And it’s not working in a South African way. It’s not benefitting South African artists or the promotion of new gallery-goers. People don’t give a fuck about art, actually. Are you telling me someone who can buy food is going to buy a painting instead? So it’s all about giving people options. We’re not Europe, and we’re not America, thank fuck.

KS: You are a visual artist, a writer, a businesswoman, a radio show host. Why put energy into so many different layers of art and activism and not just funnel your energy into paintings?

LS: I’m gifted in more than that. It’s like Wagner’s ‘Gesamtkunstwerk’: everything works together, it is just one thing in the end. Besides, I like being the center of attention too much. I can’t be in a room painting. I love speaking, and I’m only starting to understand now that my opinion actually matters.

KS: You’ve been working in the art world for a long time. How do you deal with an art world that is white, capitalist, patriarchal? Work from the outside?

LS: I work from the inside. That’s why I worked at a gallery for a long time, so that I could understand stuff. It’s also about asking the right questions and never thinking that a question is stupid. It’s about setting parameters and talking about things like money from the get-go. It’s knowing how you want to be perceived.

KS: If you were in charge of the art world, what would you do?

LS: I don’t want to be in charge of the art world. I want to be in charge of the world.