Vela Projects

04.09 - 11.10.2025

Walking into Vela Projects, the silence is immediate. The door shuts behind me, and the sounds of the city fade into obscurity. The video works pulse and ebb in the quiet antechamber, beckoning the viewer to come closer, to put on headphones or VR glasses and become utterly involved in the unfolding of the exhibition’s central theme, permacrisis, describing a never-ending period of uncertainty – something which undoubtedly characterises the modern urban condition. The world around us is constantly in flux, and the parameters of reality are never fixed.

‘Force Majeure’ explores our relationship to technology and investigates the ways in which the fourth industrial revolution has affected our collective psyche.

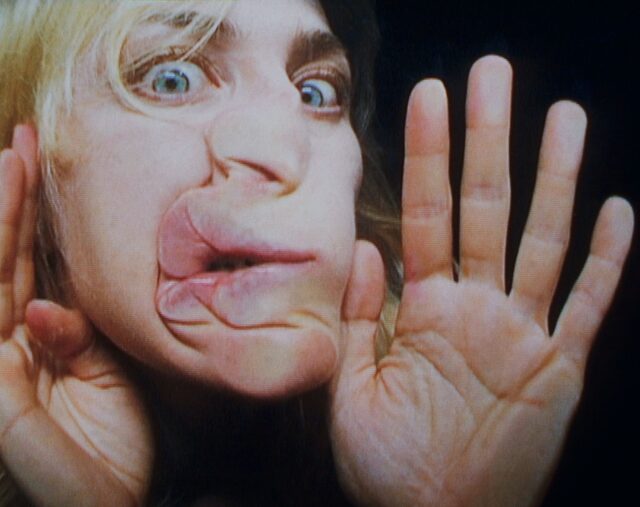

In Kristin Lucas’ Host, we see what seems to be a strange combination of a call line, game show, sports commentary, and digital agony aunt. A caller logs into a digital system of some kind, the video appearing to be from a security camera, lending the work a lo-fi, found-footage quality. A disembodied voice says, “Enter Access Code”. The caller replies, “R-E-W-I-M-O-K. Dairy free, no fish.” The characters represented in this work are shown talking past one another, attempting to reach connection but never quite managing. The character on the other line continues, “Caller, I love you.” And the caller responds, “I’ve just been feeling outside of myself.” These exchanges are strangely poignant, and they encapsulate the modern condition of endless digitisation – in our attempts to become more connected, we have lost connection altogether. Caller: “Not only did the computer shut down, but so did I. […] I went in for a tune-up, but they told me that I’m dead.” And all the while, the person on the other end keeps talking past the caller, saying things that make no sense. The sentiment, Caller, I love you, loses its meaning. Reflecting on this work, I’m left wondering whether love can real in a world where connection is unstable, unmanageable.

The references to death and digital decay in Host hint at a larger paranoia that has captured society in the digital age. Permacrisis, in this context, referring to the continuous cycles of uncertainty and emotional scarcity that we find ourselves in. The exhibition text explains the way crisis can devolve into a kind of stasis: “By some logic, then, the permacrisis becomes its own form of stability – a hypermodern diagnosis of the everyday – a chain of overlapping crises without resolution, defined by endurance, suffering, and spectacle.” The works included in ‘Force Majeure’ seem to have come out of the Matrix – faulty code holding random snippets of content together in a tenuous web of short video interactions and disconnected dialogue. The viewer’s sense of time and space shifts with each work, and the lines between reality and unreality become blurred.

In The Khuaya by Simnikiwe Buhlungu, people share neighbourhood gossip. Everyone in the video seems to know what’s going on, despite their conversation seeming otherworldly and strange. “If you close up the water, then it can’t live,” someone says. Similarly to Host, there continues to be a strange sense of misdirection in The Khuaya, the viewer becoming lost in a proliferation of missing messages and unwritten lines of code. The subjects in the video speak of mysterious holes and taps, while the viewer is excluded from the exchange, left feeling just outside of things. Once again, the possibility for connection seems just out of reach.

Tabita Rezaire’s Premium Connect is filled with epithets borrowed from the internet and pop culture. ‘Pimp UR Brain’ and other popular phrases float across the screen as the viewer is drawn deeper into a kind of quasi-spiritual awakening. The combination of the video’s digital format and the descriptions of ancient knowledge systems is strange and otherworldly. The spiritual lessons are spliced with pop culture references, perhaps watering down the message, or perhaps demonstrating the absurdity of the modern, digitised world. We are told, Rezaire’s work “embraces the idea that information systems might transcend the dichotomy of organism/spirit/device.”

There’s something about the digital spaces we find ourselves in that is at once immediate and fleeting, while also being haunted by a kind of permanency. Internet artefacts are notoriously difficult to delete, and end up existing as spectres of themselves, stored perpetually on a cloud somewhere. What does this do for our collective unconscious? How does the permanence and demand of technology affect our ability to form meaningful connections? I wonder.

Via ‘Force Majeure’, we drift through an online space that has been rendered physical. Take the VR work, The Subterranean Imprint Archive by Francois Knoetze and Amy Louise Wilson, for instance, where we are invited to participate in the multiple and layered stories that the artists are historicising. Unlike the other video works, The Subterranean Imprint Archive gives one a unique sense of agency, being the first truly interactive work in the exhibition, where the viewer’s choices affect the work’s narrative in real time. This work takes the permacrisis and localises it outside of the Western historical canon, encouraging the viewer to wrestle with the techno-positive narratives that have been endorsed by Western countries, while also interrogating the history of uranium mining in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

There are constant references to death in the works chosen for this exhibition. The digital world appears to live forever, but computers can die. And so do we. Technology can become abandoned and obsolete almost as soon as it’s created. We are forced to reckon with our own relationship to technology and to the permacrisis.