cape reviews

Running

Thabiso Sekgala at Goodman Gallery

By Anna Stielau03 May - 31 May. 0 Comment(s)

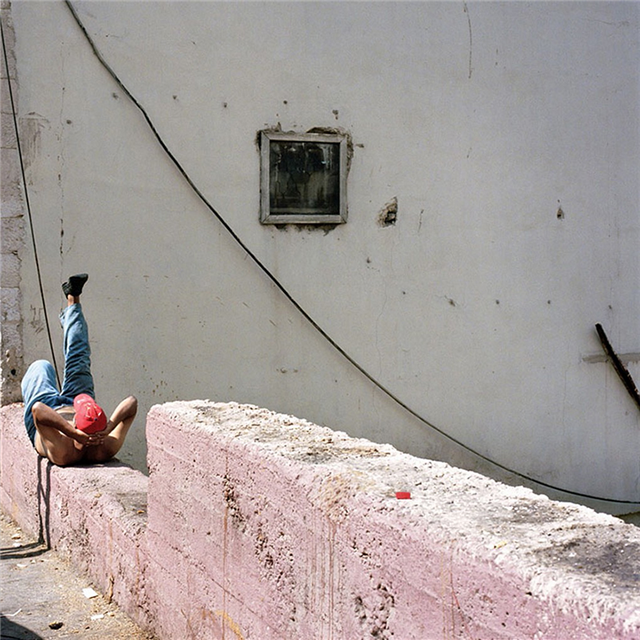

Thabiso Sekgala

Exercise, Windat, Amman,

2013.

Dibond-mounted inkjet print on fiber paper

50 x 50 cm.

The title of Thabiso Sekgala’s solo show at Goodman Cape Town, ‘Running’, is a non-finite verb form. As both a gerund and a present participle it contains within itself an infinite indeterminate space: it is unending, unbounded, forever caught in the present moment. In Gil Scott-Heron’s song Running, from which the show takes its name, these semantics are teased out in relation to the musician’s own history. You’ll have to imagine Scott-Heron’s spare cigarette-worn monotone, and the ultra-minimalist beat of this particular excerpt from his final album:

art events calendar

VIEW FULL CALENDARbuy art prints

edition of 25: R4,300.00

About Editions for ArtThrob

Outstanding prints by top South African artists. Your chance to purchase SA art at affordable prices.

FIND OUT MORE Editions for artthrobBecause I always feel like running

Not away, because there is no such place

Because if there was I would have found it by now

Because it’s easier to run

Easier than staying and finding out you’re the only one

…who didn’t run

Scott-Heron’s run came to an abrupt halt a year after that song first hit the airwaves. He died at age 62 in 2011. Framed by his life, Running’s litany of failed possibilities and justifications – the word ‘because’ repeated again and again like a prayer – becomes a post-mortem confessional. Between the drumbeats is an addict’s final plea, preserved indefinitely like an insect in amber.

That said, I’m not convinced that this reference, so dark and so introspective, sits comfortably within the white walls of Thabiso Sekgala’s exhibition. Scott-Heron is a big ghost to conjour into being. More than that, he’s a potent ideological force to invoke. His spoken-word poetry had smarts and topicality, his politics were radical and his lyricism rich. For Scott-Heron, ‘running’ was a wild and chaotic propulsion, a mad rush into the dark. By comparison, Sekgala’s ‘Running’ maintains a stilted momentum that is both elegiac and reserved.

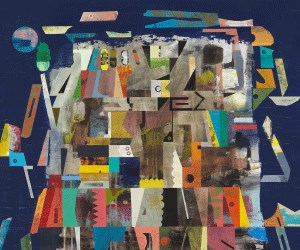

Sekgala’s photographs here are visual gerunds, of a sort. The show marries three bodies of work produced in 2013, ‘Running Amman’, ‘Running Bulawayo’ and ‘Paradise’, shot while Sekgala was on various international residencies. Without the titles on the accompanying price list, though, there is little to distinguish each series, and topographies and chronologies bleed into one another. Berlin sits beside Istanbul and borders Bulawayo. This sense of geographic universality, of indeterminate space, is compounded by the subject matter. Sekgala isolates moments that are mostly non-events. There are no sublime or momentous occasions here, just the quiet rhythms of everyday experience. Only a sense of restraint, an awkward stillness on the verge of movement, unifies the work.

Even in the case of Paradise 1 (Love near Tegel aiport, Berlin), in which running is the literal subject, all motion seems eerily truncated. Two girls, dwarfed by tall trees on either side, race toward the camera, while in the middle-ground a couple walk away holding hands. The children have been captured in a moment that seems almost choreographed, each with a left foot raised, their white clothes oddly uniform. The nearest has the word ‘love’ emblazoned on her t-shirt, but the title could just as easily refer to the lovers in the distance. The sky is a hazy band of light that demarcates the scene like a stage. The image is dispassionate, the running controlled.

Thabiso Sekgala

Kwa Tsholotsho, Bulawayo

2013

Dibond-mounted inkjet print on fiber paper

50 x 50 cm

The artist expands on his choice of title in reference to his experiences at the old Palestinian refugee camp in Amman. For him, this site in particular defined 'the idea of running'. While there, in the stillness of that indrawn international breath before America’s presumed attack on Syria, Sekgala asked himself '…will I have a place to run to?' Despite this environment, or perhaps because of it, the photographer’s desire to take cover is expertly submerged in his photographs. The atmosphere is not one of budding fear or tension. His subjects are floating signifiers adrift in an indifferent void.

Some purely aesthetic curatorial choices offer moments of anchorage. The billowing white smoke in Kwa Tsholotsho, Bulawayo is carried through in the cream car covers of Sealed, Jamal Webdin, Amman; the blue and red attire of Exercise, Windat, Amman is echoed in Inside Bulawayo Mall and appears once more in Unity Village, 6th Street, Bulawayo. But on the whole, Sekgala withholds a clear authorial position, presenting a tabula rasa onto which the viewer can project a range of possible interpretations. His images are open systems.

There are risks at stake in such an approach, too. As a strategy it can exclude rather than invite potential readings. The seemingly objective image has a great deal of historical baggage, after all. It’s a lie in which we’re complicit as viewers, agreeing to believe in the photograph as an emanation of the referent, a direct representation of the real. I passionately distrust images that lay claim to that genre of documentary photography, and there are moments in which ‘Running’ comes close to this. Beneath an impassive surface, the echoes of possible readings seem to resound in its hollow photographic spaces.

Thabiso Sekgala

Paradise 1 (Love, near Tegel Airport, Berlin)

2013

Dibond-mounted inkjet print on fiber paper

50 x 50 cm

Sekgala’s format choices in turn recall another stylistic approach. These photographs are squared off, sometimes with painful abruptness, in a manner that is decidedly Instagram-esque. The film grain and faded palette reinforce that impression, and it takes a conscious effort to remind myself that these images are not just a cross-section of someone else’s holiday, the familiar 'here’s where I ate, here I saw these children running, here I paused and peered down this alley'. That’s not a criticism, really. Instagram is a legitimate and recognisable photographic forum with a vocabulary uniquely its own. As a strategy, however, that reference does serve to further depersonalise the photographs. To invert Susan Sontag’s dictum, Sekgala’s images are all syntax, and no accent.

Somewhere in the shiny photographic surfaces I long to see the photographer more clearly reflected. In his accompanying catalogue essay, Simon Njami makes a case for another interpretation, reading Sekgala as a South African a long way from home: '[Sekgala] openly admits that, coming from Africa, there is nothing that he can expect from Europe but magnificence, beauty, and harmony. One would expect a poor African discovering Western magnificence to be overwhelmed by all those things that he is supposed to be missing back home. But here we are, confronted with a reality that has nothing to do with our expectations.' Are we? Are our expectations about Sekgala as the ‘poor African’; our expectations of Europe as ‘magnificent’? Yes, there’s an implicit disruption in naming the predominantly European series ‘Paradise’, the sheer ordinariness of its images throwing the title into ironic relief. Besides this minor intervention, the differences between these city spaces seem superficial at most. This empty chair in this quiet courtyard is any chair, every chair. This man with his back turned is crossing the street, a street, all streets. Sekgala’s subjects are, for me, devoid of expectation rather than overtly confrontational. Rather than compartmentalising city spaces, he gently and implacably locates them on a continuum.

Scott-Heron concludes Running by flipping the script on his listeners '…You’re going to know why I’m running then/You will know then, because I’m not going to tell you now.' Our access to his experience, however brief, is revoked. Perhaps therein lies the best point of comparison to Sekgala’s ‘Running’. The images invite one only so deep into their chilly and timeless spaces - their nowhere, no wheres, now/heres - and there Sekgala draws the line.

There is no such place as away.