gauteng reviews

The Constitution of Love and Loss

Zanele Muholi at STEVENSON in Johannesburg

By Michael Smith14 February - 04 April. 0 Comment(s)

Zanele Muholi

Of Love & Loss Installation view,

2014.

Photograph

.

In March, Constitutional Court Judge Edwin Cameron visited the school where I teach, as part of a programme to mark Human Rights Month. Cameron said, in plain language at the front of a school hall, without the aid of a microphone, ‘I am a gay man.’ Despite our country’s proudly inclusive constitution, which has been in place for around twenty years, and despite the wide protection that previously-marginalized groups enjoy under law, that such a simple statement of self-definition can be so electrifying clearly illustrates for me the gulf between legal and social standards.

Zanele Muholi’s latest show at Stevenson Gallery in Johannesburg, ‘Of Love & Loss’, resonated with this experience. Muholi calls herself a visual activist as well as an artist, and she has the battle scars to prove that her order of activism remains vital. A widely-reported incident in 2010 by then-Minister of Arts and Culture Lulama Xingwana at a Constitution Hill exhibition saw Xingwana walking out of the show she was supposed to open. The show included some of Muholi’s more tender images of black same-sex couples embracing. Xingwana later said through a spokesperson that she felt the work on show was ‘immoral, offensive, and going against nation-building.’ The South African Constitution, which in section 9 expressly prohibits government and private parties from discriminating on the basis of sexual orientation, was ironically absent from Xingwana’s pronouncements on Constitution Hill.

art events calendar

VIEW FULL CALENDARbuy art prints

edition of 60: R4,800.00

About Editions for ArtThrob

Outstanding prints by top South African artists. Your chance to purchase SA art at affordable prices.

FIND OUT MORE Editions for artthrob

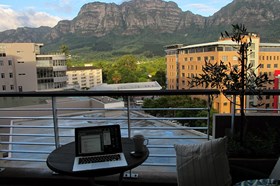

Zanele Muholi

Promise & Gift's wedding II. OR Tambo Cultural Precint, Wattville, Benoni, 2013,

C-Print,

One imagines that scars are never far from Muholi’s mind. Many of her works have dealt with difficult issues like ‘corrective rape’, an urban practice in which openly gay black women are accosted by individual or groups of men and raped, under the pretext that a ‘proper’ hetero experience will ‘cure’ them of their gayness.

It is, of course, a stone-age sensibility that violates the victims’ enshrined human rights, and yet oddly one which receives tacit social support for being more in line with ‘traditional culture’ – whatever that may be. Interestingly, in 2012, the Congress of Traditional Leaders of South Africa (Contralesa) filed a draft document calling for the removal of LGBTI rights from the Constitution of SA. It is also worth noting here that the current President of South Africa, Jacob Zuma, was one of the more vocal members of the ruling ANC in opposing the 2006 law which allowed for the legal recognition of same-sex unions.

Around this issue, there remains a constant buzz about homosexuality being non-African; this since Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe termed it so, and called homosexuals lower than ‘pigs and dogs’. One is also mindful on this continent of the perennial news of gay men being beaten and arrested for ‘homosexual offences’ in countries like Nigeria and Uganda.

The power of Muholi’s frank depictions of gay and lesbian love lies in their offering an alternative to tradition, one in which the urban homosexual subject is not bound to replicate received ideas of love and marriage. And yet, the insanity of the 'curative' rape and murder of black lesbians is met here with the normality of members of the LGBTI community engaging in the rather pedestrian pageantry of weddings. Muholi’s approach in much of the exhibition is to normalise homosexual love by showing how willing her LGBTI subjects are to participate in the rituals that usually attend straight marriage: getting one’s nails done, donning glitzy dresses and suits, posing for group photos (in one image, marrying couple Gift Sammone and Promise Meyer both lean in for a drink at a water fountain, inevitably resulting in a cheesy kiss), enduring long reception speeches by relatives who use the opportunity to tenderly tease and embarrass the couple.

Of course, as its title suggests, the show doesn’t shy away from the darker stuff. As Muholi says, ‘Ayanda Magoloza and Nhlanhla Moremi's wedding in Katlehong took place four months after Duduzile Zozo was murdered in Thokoza. Promise Meyer and Gift Sammone's wedding in Daveyton took place on 22 December, 15 days after Maleshwane Radebe was buried in Ratanda.’ In the main volume of the gallery, one is greeted by an installation of a Perspex coffin filled with cotton wool balls and strewn with dead flowers, and with a framed photo of the deceased at the casket’s head. While perhaps not the most successful piece of art - it is frankly not aesthetically commensurate with the seriousness of its concept - the work functions as an anchor in relation to which all other photographic works must be seen.

Rather more successful is an installation of 11 photographs titled Duduzile Zozo’s Funeral. One of the images in this installation shows how the public notification of Zozo’s memorial service at the Thokoza Youth Centre was pasted on a municipal electricity box, in a way similar to that done by herbalists hawking penis enlargement remedies in various commercial centres in and around Johannesburg. The effect is to replace a rampant hyper-masculinity with the tragedy of violence against lesbians and gays, and draw a discomforting connection between the two.

Throughout the show, Muholi seems to ask, rather plainly and quietly, where the liberation of the black gay subject lies. Here she seems to immediately answer herself: it is a contested plain, one on which the urban gay South African must celebrate openly and proudly, for that is better than Apartheid-era denial. But she or he must also live with the very real fear of reprisal for that celebration. This is not an unfamiliar strategy within the context of South African art history; however, within the context of South Africa’s constitution, it certainly should be.