gauteng reviews

Long live the dead Queen

Mary Sibande at Gallery MOMO

By Lisa Allan09 July - 03 August. 0 Comment(s)

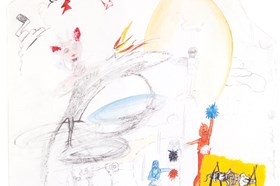

Mary Sibande

I am a lady,

2009.

digital print on cotton rag paper

62 x 60cm.

Mary Sibande’s exhibition ‘Long Live the Dead Queen’ at the Gallery MOMO in Johannesburg consists of life size mannequins and photographs thereof. The faces of the mannequins are a cast of Sibande’s own face and the figures are clothed in an elaborate hybrid of a 'maids' uniform and Victorian dresses. According to the artist’s statement, 'the body… and particularly the skin, and clothing is the site where history is contested and fantasies are played out'. The histories being played out here are the 'stereotypical depictions of women, particularly black women in our society'. One cannot deny that the figure of `the maid’ is one of South Africa’s most common stereotypes.

Stereotypes are contradictory in the sense that on the one hand they stand in for a group in the most generalised and recognisable way, but on the other hand are also invisible through the process of generalisation. The `servant’ traditionally is conceived of as an invisible, sightless, deaf and mute figure to those she serves. She has no individuality, and one of the ways this is realised is through the uniform. The uniform literally covers the body but at the same time covers the clothing of the `maid’ that might identify her as an individual who has made particular sartorial decisions.

Sibande’s 'maids' uniforms, however, have been extended and remodelled into lavish and voluptuous dresses. Sibande has used masses of tulle to create the over-feminised costume of the Victorian `lady’ as in I’m a Lady, (2009). The extravagance of the dresses disables the figures from easy movement, let alone to be able to perform the work of a `maid’. This inability to perform tasks, ironically, becomes a marker of status: a figure dressed as such would have to be waited on, her inaction indicating her position in the hierarchy.

art events calendar

VIEW FULL CALENDARbuy art prints

edition of 60: R3,500.00

About Editions for ArtThrob

Outstanding prints by top South African artists. Your chance to purchase SA art at affordable prices.

FIND OUT MORE Editions for artthrobHere the artist’s statement about the 'fantasies' of the women becomes clearer. Their elaborate outfits allow them to usurp the role of their 'madams'. Again I’m a Lady is a good example. This subversion of the social order of the 'madam' dominating the 'maid' does not however address the general social power of the colonial – and contemporary - patriarchy. Ironically the very costume of the fantasy is the same costume that maintained the restriction, and its attendant loss of power, of the Victorian body of the women of this class.

One might debate the desirability of the position of middle class Victorian colonial women: an apparent freedom is in fact not so free. Must one make the assumption that it is better to be middle class? Perhaps Sibande is not making this assumption as her concerns are rather with the point of intersection of class and race, but one senses that the crucial relationship between class and gender remains somewhat underexplored.

There are witty antidotes to the seriousness of postcolonial discourse in the form of the superman logo stitched onto the front skirt of one of the outfits, They don’t make them like they used to (2008) as well as the placement of the sign for a bus stop next to another figure The wait seems to go on forever (2009). These allusions to popular culture remind the viewer of the contemporaniety of the work, locating it in the current discourse of postmodernity.

The costumed figures have a powerful presence, especially because the space of the gallery has allowed for most of the figures to have their own room for display, which Sibande utilises very successfully. I saw the exhibition at night, and was moved by a figure/mannequin displayed in the windowfront of the gallery with strong lighting. This curatorial decision cleverly alluded to the fashion boutique window display, reinforcing the element of the works fantasy.

Accompanying the life size figures are colour photographs of the 3-dimensional works. These images provide a very different reading of the figures. Obviously one aspect of this is the very different impact they make to that of the much larger figures. The sense of opulence and restriction is lessened by the comparative size and 2-dimensionality of the photographs.

The exhibition as postcolonial 'text' references the colonial, anthropological museum display conventions. These often functioned to provide 'evidence' of the way of life of both the colonised and the coloniser. Life-size costumed figures displayed the mode of dress of the various actors in the colonial drama, the 'civilised' clothing of the Victorian coloniser contrasting with the 'uncivilised' apparel of the colonised, with the index of civilisation being the extent to which the body was covered. Sibande’s work inverts these signs through the excess of the material of the coloniser’s dress, turning reality into fantasy. This aspect of the fantasy of the maid is important in terms of contemporary South African postcolonial representation because it gives a voice to the inner life of the figure of the maid whose uniform previously rendered her invisible.

Mary Sibande’s exhibition is an interesting investigation of the possibilities of clothing as a marker of postcolonial identity that many South African artists are currently exploring.

Lisa Allan is a part-time lecturer at the University of Johannesburg and an artist.