Developing Characters: Contending Cultures & Creative Commerce in a South African Photography Studio

Centre for African Studies, Cape Town

31.07.2014- 22.08.2014

We live in the age of the selfie, where a Kim Kardashian can spend an entire holiday in Thailand seeking new backgrounds for selfies (1200 in all) destined to be made into a book for her absent partner because ‘he wasn’t there to share in the fun.’ The advent of the digital camera has given licence to all to endlessly record every plate of restaurant food consumed, every meeting of friends. Seemingly no moment is too trivial to document.

But delving into the fairly recent past – the 1950s to the 1980s – photographic anthropologists have been uncovering some remarkable caches of negatives and prints from commercial studios across the globe which, when exhibited in contemporary spaces, have focused a sharp spotlight on a different, more considered, kind of image. And far from recording an endless similarity of global lifestyle as selfies seem to do, these caches have generally reflected a fairly narrow slice of society – the community which habituated that particular studio.

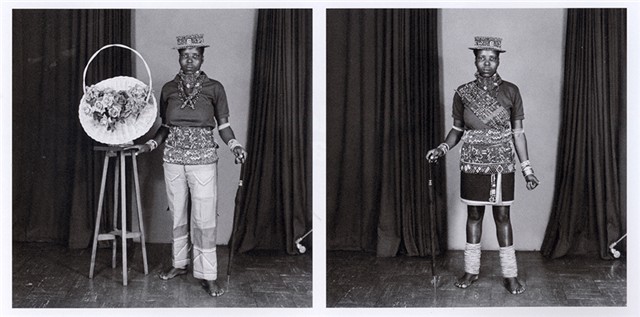

Singarum Jeevaruthnam Moodley Untitled, 1972 – 1984. Photograph

Malick Sidibe, who in 2007 became the first African to win the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at the Venice Biennale, is the best known internationally of these photographers in Africa. Closer to home, the Bobson studios in Durban’s Grey Street have yielded a rich pageant of colour drenched images of its handsomely garbed Zulu customers; colour being a technique the studio started offering in its later years.

Another such cache was recently exhibited at the African Studies Centre at the University of Cape Town under the title ‘Developing Characters: Contending Cultures and Creative Commerce in a South African Photography Studio’. The studio in question is Kitty’s Studio, Pietermaritzburg, presided over by Kitty himself, Singarum Moodley. The period covered is 1972 to 1984.

The curator of the show is New York academic Steven Dubin, who for the past decade or so has spent several months in this country each year. The 1400 black and white negatives from which the exhibition selection was made were discarded by the Killie Campbell Museum in Durban many years ago. The museum curator had originally bought the collection from the Moodley family, after Kitty’s death, then extracted those most pertinent to Zulu traditional culture for the museum. The discards were taken by an intern, and after many years of being packed away in a Johannesburg garage have resurfaced, and been cleaned, researched and printed up by Dubin.

Singarum Jeevaruthnam Moodley Untitled, 1972 – 1984. Photograph

The slice of life, presented by the 80 photographs, is both intriguing and engaging. As we learn from the informative catalogue, Kitty’s was located in the heart of the city, on the first floor of a building next to the taxi rank. ‘Suggestive of African-American barbershops, it was also a place were men such as the young Jacob Zuma and Masiuoa “Terror” Lekota hung out, read newspapers and shared tea, argued over politics and soccer while relaxing on benches placed upon the broad balcony outside the shop,’ writes Dubin.

The studio did not provide props, and people brought the clothes they wished to wear and any extra accessories to be incorporated into the portrait – thus, the title ‘Developing Characters.’ Kitty’s backdrop was simple. Most of his subjects were photographed against an interior wall in a space between two curtains. Floor coverings seem to alternate between Marley tiles and a patterned carpet, although perhaps one surface superseded the other over time. After that, it was up to Kitty’s subjects to add their own drama to the shot.

A particularly interesting pair of images shows a Zulu woman appearing first as one gender and then the other – swopping her skirt for a pair of trousers described by the curator as ‘the stylish kind of pants that amaZulu men have typically reserved for dancing and courting for decades.’ Dubin told me that Zulu women shown the pants version within the past year were shocked that a woman would wish to have herself photographed in this way. One thinks here of contemporary photographer Zanele Muholi whose activist work includes presenting images of black lesbians to confront our society in which, despite a constitution declaring freedom of sexual orientation, prejudice is all too common. One raises a glass to this early unnamed pioneer.

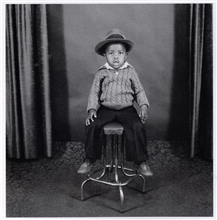

The photos of small children all decked up in their best are charming, although most of them look terrified to find themselves perched in the strange surroundings of the studio. Sportsmen, nurses, young lovers, friends, factory workers dressed in their best for ‘going away day’ – December 15, which marked the onset of the Christmas holidays – all form a part of Kitty’s passing parade.

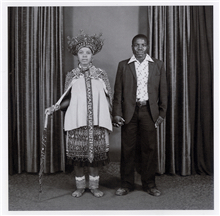

Singarum Jeevaruthnam Moodley Untitled, 1972 – 1984. Photograph

Deconstructing the social codes underlying some of the photographs would require serious research. Why is a wife dressed in traditional beaded garb while the husband whose hand she clasps is clad in western clothing? Does the lettered ‘tongue’ around her neck spell out a message for him or for the family who presumably are the intended audience for this photo?

Although the catalogue is helpful, there is much which cannot be contained in this small format, and a planned book on the collection is something to be anticipated. One hopes too that although the photographs may well find an appreciative international audience, a complete set will remain here in South Africa, part of the heritage which includes the Drum images, and such photographers as Eli Weinberg, Ernest Cole and David Goldblatt.

Kitty would probably not have seen himself in the activist role which those great photographers embraced, but nonetheless his modest but lively images, which included members of every race group, are an exciting addition to the national archive, and have opened the door to life in a particular corner of the sleepy city of Pietermartizburg at a time when apartheid was at its height.