Iziko South African National Gallery, Cape Town

02.06 – 24.08.2019

Something funny happens when an artist slips into the ‘Established Artist’ box. It appears that their name casts an obscuring shadow over their work. It does not necessarily make the work better or worse but rather, on some level, invisible. It becomes difficult to see past their public persona or their ‘signature’ style, to look at their work with any real depth. The effect varies: for some artists, we nod in admiration at the sight of their names, for others we roll our eyes, “Them again.” David Koloane, as a person and as a persona, is well-loved. The impact his work has had on the art world, as an artist, writer, and mentor, is profound. While this legacy is important, it does mask the complexities that existed within his artistic practice.

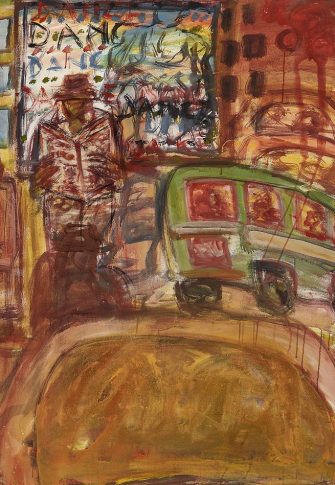

This effect feels amplified by his passing shortly after the exhibition opened. A good retrospective resurfaces the complexities that exist within the Established Artist’s work, something that ‘A Resilient Visionary: Poetic Expressions of David Koloane’ achieves, largely through its width and depth. It shows us the work we might have never seen or expected from him, if we have been drawn in by the narrative created by his reputation. For me, hearing the name ‘Koloane’ invoked visions of brash, emotive depictions of urban life in Johannesburg with an emphasis on line, colour, and empathy. It is difficult to resist the urge to essentialise artists’ practices to flash card levels of simplicity. While I didn’t leave the National Gallery feeling as if my mental image had been erased, the exhibition made it more detailed and elaborate.

Delving more deeply into the different periods of his practice is especially important in Koloane’s case, as he experimented with medium and form throughout his career. In an interview I had with him in 2016, he emphasised the playful nature of his time in his studio at the Bag Factory, a compound of artist studios which has supported the practice of emerging artists in Johannesburg, and which Koloane co-founded in 1991. The placement of his own studio amongst those of young artists was indicative of his own attitude towards making. As stated in that interview, when he began his work as an artist, it was with the intention that his education and a more traditional profession, such as teaching or journalism, were his future, with art as a hobby, “something to do over the weekend”. The idea of being a professional artist was radical at the time. His attitude towards art-making changed when school friend, artist and mentor Louis Maqhubela encouraged him to think of his artistic practice more seriously. I point out this transformation as I believe it says something about the professionalisation of art and the art world in South Africa, which Koloane himself partly spearheaded. Does a tension lie between experimentation and professionalisation, which encourages ‘flash card thinking’? If so, what does that mean for the way we produce, exhibit, and write about art in the contemporary context?

The exhibition shows that Koloane himself was not entirely, if at all, restrained by this tension. Rather than placing all emphasis on his more familiar figurative painting, it places his assemblage and abstraction, as well as an animated video, alongside. The assemblage works in particular were a heartening surprise for me and likely many others, as they are less widely and recently exhibited than his other paintings. Works such as Mystery Box (1990 – 1999), are evocative of artefacts submerged in primordial mud, excavated by erosion. The everyday nature of the objects, a whole saxophone, studio tools, letters and other ephemera, held together with a thick shellacking of a brown varnish also suggests an attempt to memorialise the moments lived in and out of the studio. Archiving and history-keeping was especially crucial for black people living through the Apartheid government, as they bore witness to the ability of colonising people to undermine and eradicate existing histories, and the impact that this eradication could have on the sociopolitical landscape and on individual psyches. But it is also beautiful as a celebration of Koloane’s love of making, of his radical act of being an artist.

The other celebration present throughout the exhibition is of Koloane’s empathy and sensitivity, most apparent in his figurative paintings. His depictions of all manner of life, of sex workers, street hawkers, jazz musicians and barflies, with the urban space as their ecosystem, highlights his love and understanding of people, in joy and in suffering. One gains the sense that they are not just subjects to him but also lives that he seeks to know more of.

Included in the exhibition is an animated video, The Takeover (2016) depicting the occupation of an empty primary school by a rabid pack of dogs, who attack and kill a woman passing by, and who are driven out by an angry, township community. He had described the video to me in our interview, shortly before it was exhibited at Goodman Johannesburg. I was struck by his account of the story that he had read in a newspaper. He retold the report as if he had lived it. It was a moment that hinted toward his vast reserve of empathy, which can be felt throughout the retrospective and his wider career.

In other works, such as The Journey 13 (1998) which shows an abstracted body lying naked and curled up, we are given greater knowledge of Koloane’s sense of interiority. This interiority is further explored in his more recent works, such as Abstracted Compositions III (2019) and Dancers I (2019) which both depart from his earlier journalistic depictions by projecting and intermingling his inner world on to the world as he sees it. This is especially moving in the Flight series which shows a riotous wave of white and grey doves mid-flight, with expressive beaks and beady eyes startlingly placed. They have a meditative, existential quality and, perhaps under the influence of the news of his passing, I saw an exploration of mortality.

The Iziko South African National Gallery‘s retrospective succeeds for me, as it does not offer just the greatest hits, but also the deep cuts. It would be difficult to leave having not learnt anything about Koloane and the aesthetic and social concerns expressed within his work. In terms of order, the show does not always feel as if it is telling a clear story, although that may be preferable for the kind of visitor who likes to be free to make their own narrative line in an exhibition. Even so, I wonder how accessible the presentation is to a visitor who is unfamiliar with Koloane and South African art in the 20th century. That said, the scope of the work shown is an achievement in and of itself, imparting knowledge of an important artist which feels long overdue.