Michaelis Galleries

14.02 - 24.03.2020

The UCT art collection was founded in 1920. In 2016, close to a century later, the collection consisted of 79% artworks by white artists. 2016 – when breathing was particularly difficult – was the height of the #feesmustfall movement and the point at which the decolonial discourse was brought into the general consciousness of students across many South African universities. The period marked an important moment in the interrogation of what was otherwise an uninterrupted and undisrupted South African art canon. A lot of us had been indoctrinated into thinking of artworks (and collections of artworks) as apolitical but in fact, many collections are imposing, biased and incomplete. This often plays out in the representation, promotion and valorisation of the dominant culture. We’ve come to know better, we’ve come to understand that the dominant culture does not lend itself to syncretism.

When we think of art collections, we’re referring to objects that have been selected, conserved, accessed and circulated as art but we’re also talking about authorship and authority through processes of selection. In his 2002 text, The Power of the Archive and its Limits, Achille Mbembe writes, ‘The archive, therefore, is fundamentally a matter of discrimination and of selection, which, in the end, results in the granting of a privileged status to certain written documents, and the refusal of that same status to others, thereby judged “unarchivable”. The archive is, therefore, not a piece of data, but a status.’

Mbembe’s thoughts on how documents are selected into an archive are instructive and can be extrapolated to thinking through selection of artworks into a collection. Collections are fundamentally a matter of discrimination and of selection, granting privileged status to some while refusing the same status to others. By understanding the implications of processes of selection, we better understand why many Black artists assert their right to be included in various spaces of power.

The exhibition ‘We’ve come to take you home #1’ serves as a reflection point to events of the #feesmustfall movement, transformation agendas and the broader discussions on institutional exclusion and racism. It showcases a selection of artworks by twenty-two artists whose works have been acquired into the UCT art collection in response to the findings by the UCT Works of Art Committee. According to the curator, ‘the exhibition seeks to showcase the germination of transformative and inclusive art collection practices which UCT, through the Works of Art Committee, has committed itself to’. The exhibition begins the important job of giving account to the contributions of Black artists who were previously structurally excluded, by centring their work and allowing them to be engaged with critically. In a sense, the exhibition walks alongside ideas of resistance and refusals (a refusal to be excluded, disregarded) and serves as a conduit for the reconstruction of collection practices. It also offers an opportunity to question the responsibility of institutional collections towards artists, the art community and society, particularly to the extent that these collections influence our public imaginations of heritage and legacy.

Thinking through the exhibition, it is this idea of inclusion and inclusivity that I grapple with. Perhaps this has to do with my ongoing obsession with the insider-outsider question (which for the most part remains unresolved), coupled with the exhibition title which evokes ideas of safety, comfort and acceptance. I find myself struggling with what “we” refers to. I find myself struggling with the person assigned “you”. I find myself struggling with the space between the two words. Who is deciding who gets to go home and if it really is home, why does it need to be negotiated with?

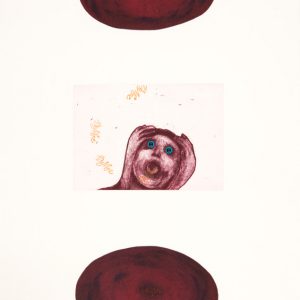

In the same light, I understand the value of including artists who have previously been excluded into these spaces. Their presence, if nothing else, problematise such spaces and goes a long way in countering master narratives of supremacy. This act of inclusion allows us to reclaim lost canons. In this exhibition, Helen Sebidi complicates notions of modernisms with her lithographs; (Talking to the past, 2008) and (After Lobola (Married), 2008), Maurice Mbikayi strips abstraction to the essential elements of the line with his use of computer cables (Untitled, 2019), Mashudu Nevhutalu engages narrative through earthy hues (Festivities, 2019) and Malwande Mthethwa questions knowledge (ulwazi) through textual inscriptions (Bathi Ingcazelo Iyisdingo Series, 2018). It is in trying to translate Mthethwa’s works for myself that I again realise the pertinence of exhibitions like these. After multiple back and forth messages via Whatsapp and the help of a friend I settle on ‘Knowledge travels, it travels to me (reaches me). Might it never stop. May it continue’—Ulwazi luhamba luhambe lufike kimi. Malungami. Maluqhubeke.