THEFOURTH

10.12 - 28.02.2021

The Spectacle comprises of various themed rooms filled with objects that cohabit, but also seem to float in, space – three-meter-high neon arches, an orange plastic cactus, plush copies of Dali’s lip sofas, industrial carpet on the walls – coalescing to form a surreal environment.

The show takes its name from Guy Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle, a text interrogating the effects of the burgeoning capitalism in post-war Europe. Here, appearance and representation have superseded reality; “life is presented as an immense accumulation of spectacles.”

I am drawn by the carpet, rough and black, like a car mat. Ugly, I think and rub it appreciatively. The work of Unathi Mkonto, the squares of fabric press close together like the pages of a book. It is a critique of segregation and exclusion in urban planning, I am told. Next to this is a frame filled with pink and red hard candy lips, sticky and transparent, so bright they’re hard to miss. The pop punch of the lips had already overpowered the seriousness of the carpet. It’s all so aesthetic, I find myself thinking. Where is the unsettling, the challenge, the movement, that makes my stomach hum or turn?

As Debord writes, the spectacle takes in fragmented views of reality and gives them unity, to create “a separate pseudo-world that can only be looked at.” The Fourth succeeds in this. Art objects mix with design objects, in a very chic apartment on the fourth floor of a restored art deco building. It overlooks, in more than one sense, the stall holders and foot traffic of St George’s Mall below. Yet, in line with Debord, The Spectacle’s catalogue presents the show as a critique of capitalism.

Galia Gluckman, Cape of Good Hope, 2020. Angel Hair and Bonding Tape on Wire Mesh, 160 x 220 cm,

The Colour of Life, 2020. Paper, Acrylic, Mirror, Angel Hair, Canvas, Sequins and Bonding Tape on Moulded Cap, 30 x 60 x 30 cm

In The Red Room tinsel sculptures from Galia Gluckman hang from the ceiling and on walls, which are painted the colour of a Santa costume. It is immersive, shimmering, seductive. The cape of good hope, a tinsel garment, worn by a nude model on the opening night, glitters darkly. The show’s catalogue states a desire to radicalise and improvise new interpretations of Christmas, an event during which the state, church, family, and consumerism perfectly align to continue the spectacle.

Some of this is re-imagining is taken up in the exhibition: sculpted candy canes on a side table; a fan with shoelace aglets striking a single note on a toy xylophone; a canvas bearing the capitalized words: How Many Homosexuals Does it take to Build a Home; a painting of a cross over the words Mother/Father/Son. While one can question the expulsion of queerness from the home space or subvert a sacred religious (and familial) hierarchy, the society of the spectacle remains immune to subversion. This is a central tenet of Debord’s theorization: any critique or resistance is subsumed, trivialized and spectacularized, thereby nullifying its disruptive potential and using it to continue and support the current system. Placing counter-normative narratives in a commercial space renders them impotent.

On a shelf in The Portrait Alcove are a set of colon statues – figures which originated in West Africa as a critique of colonial officials, but are now familiar characters in tourist markets here. The statues have been sliced lengthways, the front half inverted and reattached as masks. This grotesque parody by artist Steven Sack intends to interrogate the way we identify with or distance ourselves from other cultures. Yet, the violence done to these objects shows how whiteness leverages the spectacle: the appropriation of cultural objects reiterates the very power dynamic the work might seek to contemplate.

Brett Charles Seiler, The Rainbow Will Always Be Above US, 2020. Bitumen and roof paint on canvas, 72 x 67 cm

Not only is the spectacle “the model of the prevailing way of life,” it is also, “[i]n both form and content… a total justification of the conditions and goals of the existing system.” Having a room called The Shop is somewhat redundant as everything is already for sale, but here art is shown as a consumable object, above all else. On the ceiling of the Christmas-Bed Room, a roughly painted, cold-eyed businessman stares through the words: The Rainbow Will Always Be Above US. Indeed, even the most critical and disruptive pieces of art may end up as an asset, an investment.

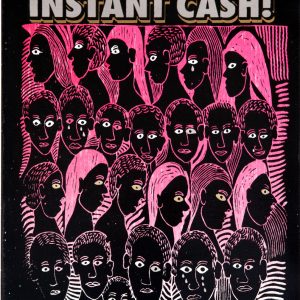

Next is The Billy Bar, decorated with photographs by Billy Monk. The low-light intimacy of the bar brings the images to life: queer folk, sailors, sex workers and lusty couples enjoying the freedom and pleasure found in the underground Catacombs Club, where Monk worked as a bouncer. These images are radical: dating from 1967, the flash exposing people over whom, for a moment, apartheid’s restrictions seem to have no hold, Yet, in this private bar

for patrons of the gallery, the historical and political significance feels dimmed. There is also pleasure, the textures say, the colours, the chairs. Sit down, they say, make yourself comfortable.

Debord argues that we all participate in the continuation of the spectacle. This show reflects the privilege and pleasure found in its artifice: the pleasure of having and participating in that space, which sustains our belief in it. There is even something poetic in the claim to critique, through spectacle, which consumes and collapses in on itself, endlessly reproducing and leaving us relentlessly enraptured.