For many of us, the place we call home is laden with danger and violence. The ghetto, township, eKasi – these are the places that moulded us and made us into who we are. But they are also the places that break us.

The place you call home can instruct you. It can show you how to behave and can remind you of your assigned position. A place represents not only its history (read: apartheid spatial politics), but also the ways in which futures are made there. The trouble is how to speak about the difficulties of where we come from, without perpetuating the violence of the coloniser’s language—frightening, sordid, wild. Warren Maroon reflects on the Cape Flats to understand something about gang violence and comes out the other side with a graceful language that inspires deep contemplation.

In the exhibition Reverence, he presents three works that hover between sculpture and installation. The exhibition negotiates chaos between violence and vulnerability through memories of his childhood in the Cape Flats. Meaning rests both inside and outside objects – a longcase clock, roses, lit candles, broken bottles and bricks – as they are used in unfamiliar ways to codify social systems. Through the use of the readymade, Maroon peels back layers behind narratives that glorify gang culture, championed by mass media.

Maroon recalls the release of the 1993 crime drama, Blood In Blood Out – which details the lives of three gang members in East Los Angeles – as a pivotal moment in his view of the media’s impact on kids in his neighbourhood. He notes, “So many gangs spawned in my neighbourhood. Kids thought about their positions differently. Everyone wanted to climb the ranks, at which point they started to glorify gang leaders and hitmen. If a child looks at a hardened criminal as a role model, something failed somewhere.” This memory of a marked shift in collective behaviour lingers in the artist’s mind and is reconstituted as an investigation of violence through sound, movement and light.

Sound — to sound out, resonate, resound, emit vibrations that travel through time and space.

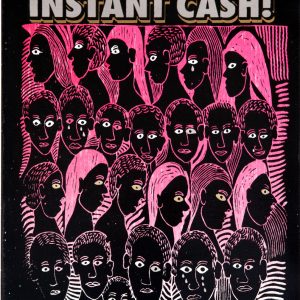

- Warren Maroon, A Thousand Tongues, 2022. Courtesy of Church Projects.

- Warren Maroon, A Thousand Tongues, 2022. Courtesy of Church Projects.

In A thousand tongues, fresh red roses are arranged in a grid that cuts through a pane of glass. The abscission of rose petals captures anxieties around decay and loss, reminding us that time cannot be defeated. The raspy and indistinct intonation of Sabela — the language originally developed inside South African national prisons as a means of communication among gang members — fills the room: a breaking tongue, a thousand broken tongues, a dialect of brokenness whose phonology and syntax melds Afrikaans, isiZulu, isiXhosa and English. Unintelligible to the uninitiated, Sabela infers the textuality governed by “die boeke” (the books) from which gangsters quote and share phrases. These are mantras bound and solidified in blood, scripture-like sayings that build a call and response narrative of the myths of Nongoloza and Kilikijan, dubbed the fathers of 19th century gangster systems.

Light — illuminate, ignite, burn

In All that glitters, broken beer bottles are balanced on a wooden footstool. Some are rimmed with gold leaf, some are stacked, and five carry lit candles. A laced fabric is folded a few metres away to complete the work. These layered elements evoke the grief experienced by communities touched by gang violence. The work strongly resembles the ubiquitous brown tumblers found in many coloured homes, perhaps as a reminder of the seepage of gang violence to the home space. This shrine-like work also takes on a sharper resonance to the communal “Mandrax circle,” where users crouch together, kneeling almost as if in prayer, passing the smoking pipe in (un)holy communion. In another sense, All that glitters recalls the countless lives of gang members and innocent victims lost in the pursuit of the gold that Nongoloza and Kilikijan were chasing.

Movement — change, drift, fall

The threat of gangs is a reality for many young men of colour, who are often recruited at an early age into a life-long commitment. Escape is almost impossible, and so the cycle of violence continues. In Alpha and Omega, a longcase clock stands in the middle of the tiny upstairs room of Church Projects. Fragments of bricks are placed at its foot. Slender pieces of wood of varying lengths are installed to resemble clock hands – they tick but do not turn fully clockwise, unable to move time forward. The work is a reflection on gang systems that run like clockwork: the youth are stuck in a loop of violence.

In this exhibition, Maroon questions where the youth place their reverence. Against the grain of violence and death, Maroon reconfigures sites, symbols and customs entrenched within gang systems to point to their dangers and complexities. The power in Maroon’s work lies in his ability to dig out the ugly and dangerous to initiate difficult conversation through care and subtlety.