SMAC Gallery

27.08 - 14.01.2023

Concrete and steel define the structure of urban life. We live and work and sleep on foundations of concrete, while steel beams and rods keep the walls and roofs in check. To work in this medium is to confront permanence and brute force. Ledelle Moe’s sculptural work, comprising a large reclining figure and installation of smaller works, shares the language of the monumental while asserting something more contemplative and provocative.

When entering the exhibition, the dominant impression is the timeless quality of the works. These figures could feel at home in a museum collection of Paleolithic artefacts. The smaller forms mounted on the wall share the language of stone age tools and appear like a cloud of burnt out stars. The reference to space and constellations is also observed in the artist’s notebooks, displayed in the same room.

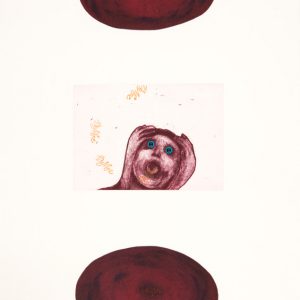

The notebooks offer an insight into the artist’s research and thinking, but it is the drawings that reveal an unflinching insight into her study of the human form. Here, we are confronted with visceral depictions of the solid fact of living in a body. Like her sculptures, these drawings are simultaneously heavy and light. Thin, delicate lines describe a seated figure whose head is darkly shaded. The lack of identity suggests a withholding of detail, or perhaps a violent erasure. There is also the figure with multiple limbs that appears like a dancer frozen in strobe light, or the site of struggle.

In contrast to the drawings, the lack of limbs and movement in the sculptures forces the viewer to concentrate on the possibilities of solidity. With the largest sculpture, it is intriguing to encounter the female form as monolithic and unmoving. The large sculpture rests alone in the room, while those in the next-door room exist in community. Some of these smaller sculptures are embedded with stones and evoke the idea of forms that are born and not made, as is prized in the tradition of Zen pottery. This quality emphasizes the timeless quality of the forms. Like ceramic, concrete is similarly a material of the ancient world. But unlike clay that requires firing, the sculptures on display are cured by contact with air. This fact is cause for thought. The simple act of breathing solidifies our presence, our material existence and ultimately our demise. And yet, unlike us, concrete continues to get harder as time passes.

The contemplation of the simple fact of embodied living is something we rarely do in our contemporary time. The proliferation of mindfulness apps is one indication of the consequences of superficial, fast-paced living and speaks to our disregard for our bodies beyond how to tame and mould them.

Modernity’s unease with the physical body saw not only the Cartesian divide of spirit, mind and body but also categorised women’s bodies as animal, uncontrolled or insane. Moe’s large figure is serene, unapologetically full and forceful. While recognisably female, this body is not concerned with narratives of beauty. This figure is not the sensual nude of western art history but something ancient that came before modern women were dispossessed of a connection with their bodies. The head is the high point of the sculpture and is held up by the strong curve of the back, shoulders and neck. While lying down, this figure is not reclining or passive. Moe’s work speaks an older language of stone implements and a culture where women were worshipped for their ability to reproduce. In other words, the sculpture alludes to a time when bodies were valued for what they could do, rather than aesthetics.

While unrelated to Moe’s concerns, Tracy Emin’s recent monumental sculpture, I lay here for you, shares this affirmation of the female body. Emin’s provocative work reflects her recent experience of recovering from cancer, confronting illness and the loss of body sovereignty. Emin also speaks to her life stage as a single, aging woman without children. Her work explodes ideas about sexual agency and desire from the perspective of a woman who has become invisible in western culture because she is no longer young and beautiful. I am juggling these thoughts while looking at an image of Ledelle Moe’s large work stuck above my desk. I cannot help but return to questions of representation. The work is powerful but quiet. An ur-woman who survives despite the banal routines of life, despite abuse, despite the indignities of illness and age. Moe’s female figure lies godlike, a seed of the future.