Stevenson; blank projects, Cape Town

21.07.2016 – 27.08.2016

As homage to the life of author K Sello Duiker, ‘The Quiet Violence of Dreams’ exhibition manifests an admirable interdisciplinarity of visual commentary on written text. The exhibition functions as a collective response to Duiker’s 2001 novel of the same title and explores ways in which the artists relate, reflect and project their experiences onto a piece of writing. The story follows the life of Tshepo, a young man of colour recently released from a mental institute after being admitted for psychosis. The novel follows him through Cape Town and its surrounds, and vividly explores his journey of questioning and understanding his sexuality and masculinity as a black man in post-1994 South Africa. The novel could be read autobiographically, as the author and main character have many experiences of institutional violence in common. After reading the novel, the artists selected by Joost Bosland created and contributed works relating to narratives and experiences that spoke to them. In addition to these responses, some pre-existing works were chosen for their relevant commentary on themes prevalent in the novel, demonstrating the almost non-fictitious nature of the novel.

The Quiet Violence of Dreams spreads across three galleries in two cities: Stevenson Cape Town, blank projects Cape Town, and Stevenson Johannesburg (which I was unable to attend). Upon my arrival at Stevenson Cape Town, the foyer sits heavily decorated with rose petals on the floor, fallen from a nest of roses hanging from the ceiling. Jody Brand’s #SayHerName installation gently invites the viewer to the show with poignant beauty. The title references a hashtag which grew as a response to continuous unsolved murders of queer women of colour in America. By saying their names we make present what usually goes by unseen. In reference to the unsolved murders of sex workers in Cape Town, as well as the antagonism experienced by Tshepo in the novel, Brand assertively addresses the reality of violence against black and brown queer bodies. Brand’s second contribution in the next room, O, presently I’m Standing, dominates the space as a 3-metre tall photographic print of a black woman in a bathroom at a party, wearing only underwear. Breasts exposed, her arms raised to an ornate gold chandelier, Samkelo unapologetically confronts the eye of the Stevenson guest. By demonstrating her power through vulnerability and self-love, making seen what usually goes unseen, she weaponises the body politic in a white-driven capitalist patriarchy.

Robin Rhode’s Gun Drawings is a series of eight charcoal drawings, each a rough depiction of a handgun with handwritten text included underneath. Naming some of South Africa’s most well known gangs such as Hard Livings and The Americans, this is a reference to Tshepo’s roommate, Chris, who is an ex-Pollsmoor convict. Chris is a character whose actions demonstrate the multiple outcomes of violence. While unapologetically committing brutal criminal acts, including a gang rape of Tshepo, he displays broken pride, unsure of whether or not to play the victim or continue his fight for survival. With his simple hand-drawn sketches, Rhode illustrates an eerie casualness in relation to violence in gang culture, which informed the curators’ choice to include this as a demonstration of Chris’ attitude towards his actions and betrayal of his friend.

Buhlebezwe Siwani, Ithongo,2016. Umkhando pigment, government-provided bedsheets, paper. Dimensions variable

The larger middle room of the gallery has half of its entrances curtained off, with dark grey walls and dimmed lights. This makes viewing of the videos much easier and allows for dramatic lighting of the other installations in the room, creating an atmosphere of deep intensity. Vivid red umkhando pigment glows from the floor in Buhlebezwe Siwani’s installation titled Ithongo. The pigment is separated in small mattress-sized compartments by bed sheets that were illegally acquired from a state hospital. Ithongo is an installation recording of Siwani’s site-specific performance Umthakati Akalali where over a span of 17 hours the artist slept and every hour woke up to imprint her face with umkhando on the pages hanging against the wall. Tsepho’s narrative is heavily influenced by his experiences of psychosis as well as being in solitary confinement in a mental institution. Drawing on her practice as a sangoma the artist uses umkhando, which is a pigment usually used in rituals of spiritual healing, and compares this to the supposed space of healing presented by mental institutions. Yet in her performance of intermittent sleeping and by lying on new sheets each hour, Siwani re-enacts a state of delirium and displacement similar to what is experienced by Tshepo.

The novel’s characters demonstrate vulnerable self-exploration; people who desire a safe personal space. Across the road at Blank Projects, Glenn Ligon’s neon installation Untitled (Bruise/Blues) fills the entrance room in a blue glow with the words ‘Bruise’ and ‘Blues’ hanging back-to-back from the ceiling. The flashing neon immediately evokes police presence, or even the governmental ‘Blue Light Brigade’. With this, the artist creates an environment commenting on police brutality and institutional violence imposed on the displaced people of Woodstock and its surrounds, since the opening of the novel is set in Woodstock Main Road, right outside where the Stevenson is.

Akram Zatari’s video How I love you similarly functions as a portrayal of governmental infringing on sexuality and body-policing and speaks about the challenges of being gay in Lebanon, a country where gay marriage is illegal and non-heteronormativity is frowned upon. The video displays a computer chat window with anonymous users planning hook ups, and showing various anonymous figures discussing their experiences of homophobia, violence and sex. The figures are either out of focus or over-exposed to illustrate the necessary secretive manner in which they need to navigate their lives to share some intimacy, much like Tshepo using his ‘Angelo’ alias as a sex worker.

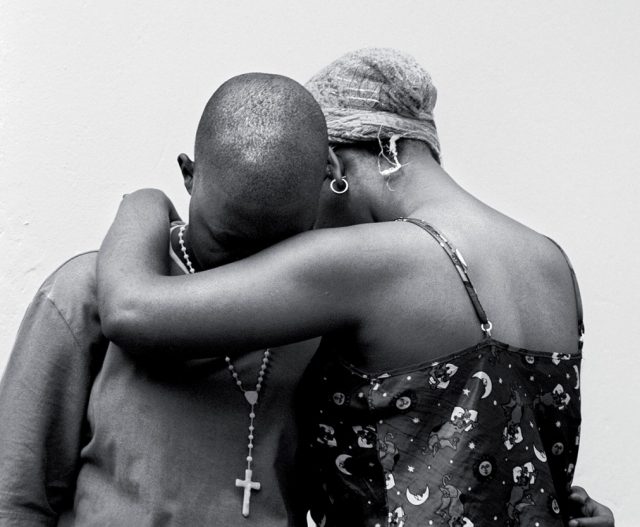

Another side of the queer experience is depicted in Zanele Muholi’s series Only Half the Picture. Using her work as social documentary, Muholi’s series depicts the injuries of hate crimes performed on queer and femme people of colour in South African townships. Juxtaposed with portraits of love and intimacy between queer couples, the artist reflects on Tshepo’s experiences whilst demonstrating tenderness and pain in a country that prides itself on diversity and inclusivity. This in turn reiterates Brand’s foyer installation across the road.

The institutionalisation of our experiences runs as a consistent theme throughout the show. For Kemang Wa Lehulere’s work Once bitten, twice shy, the artist uses remnants of old school desks and rebuilds them as five separate holdings for dentures modelled off his own teeth. Clamped within the grasp of these teeth are small books covered in 22-carat gold. Through the wood, old and ridden with graffiti, the artist speaks to the condition of education and schools in this country. Whilst not a reference to the novel itself, this work was chosen by the curators as an extension of the cultural landscape within Tshepo’s narrative: the books, intended to be printed versions of our constitution, imply the desired freedom and peace of the Rainbow Nation. These treasured golden constitutions are seen as trophies of democracy but instead depict the atrophy and underdeveloped service delivery of a post-apartheid legacy.

With a myriad of works extending over three galleries, it is a challenge to concisely address each artist and their lived experiences. Since certain narratives and themes reflect differently in our own perceptions it might also be interesting to note how the Stevenson galleries have orchestrated an exhibition of such personal narrative. The commercial aspect often present with the Stevenson is certainly subdued with no mention of prices. Each of the works is paired with a label identifying the relevant narrative, linking the novel to the exhibition and suggesting a direction of thought to the viewer. This exhibition evidently pursues an effectively powerful agenda of personal pain.

As evident as it is that we live subjective experiences, interpret texts in our own way, and express our work individually, one thing this exhibition surely makes clear is that certain experiences are shared because institutional systems are put in place. The stories told by Tshepo manifest from Duiker’s own life, and the artists themselves experience many of these stories as well. Though the novel was written fifteen years ago, it serves as a portrait of contemporary South Africa and is evidence that the dream of post-apartheid has embodied itself for many as quiet violence.