Norval Foundation, Cape Town

29.09.2018 – 21.01.2019

‘The light is taking me to pieces.’

Moving towards the centre of the elaborate maze-like structure which occupies the Norval Foundation’s sprawling Gallery 8 space, the viewer is confronted by a towering, skeletonised figure. Perhaps it’s the result of this sculptural installation – entitled Studies for the Garden of Earthly Delights – working in tandem with the comic book aesthetics of Wim Botha’s 2009 work Joburg Altarpiece (which now resides on the exterior of this structure), but this encounter irrevocably feels like an homage, if not a recreation, of a specific panel in author Alan Moore and artist Dave Gibbons’s hugely influential 1987 graphic novel Watchmen.

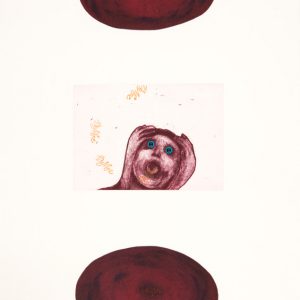

Panel from Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons, Watchmen, 1987 (left), and detail from Wim Botha, Studies for the Garden of Earthly Delights, 2018 (right).

The panel in question depicts the moment in which nuclear physicist Dr. Jonathan Osterman is trapped in a fictional machine called an Intrinsic Field Subtractor and is obliterated by radioactive light, removing the ‘intrinsic field’ which holds his atoms together and causing him to disintegrate. Over time, Osterman’s consciousness is able to reassemble itself at a molecular level, and he is reborn as the blue Übermensch Doctor Manhattan, complete with a host of nifty superhuman abilities. Viewing this selection of Botha’s seminal works within a retrospective context in ‘Heliostat’, it strikes me that this idea of an intrinsic field –as a catchall for the fundamental forces which hold something together – is a great metaphor for what Wim Botha’s work has been about all along.

This observation is not limited to the works with obvious visual parallels, such as the afore-mentioned Joburg Altarpiece (wherein various European art historical works by Velázquez, Rubens, et al are subjected to similar skeletonising blasts) and the appropriately titled Blastwave I-V series from 2005 (which does the same to a Pierneef acacia). Within the context of Botha’s work, the ‘intrinsic field’ is a decidedly Platonic entity, the fundamental truth of something once the surrounding matter is taken to pieces by the light. This fits in snuggly with curator Owen Martin’s astute usage of refraction – understood as the transformation of light by passing it through various materials – as the central framing device of ‘Heliostat’.

Wim Botha, commune: suspension of disbelief , 2001. Bibles, surveillance equipment, steel.

Installation view: Norval Foundation, 2018

As such, the exhibition is particularly effective at bringing Botha’s fascination with disassembly and reassembly, component parts, and gestalt recognition to the fore. Viewing a work such as commune: suspension of disbelief as refraction shifts the focus substantially. While the overtly subversive or iconoclastic elements which have dominated readings of the work before are obviously still very much present (the Vader kyk surveillance cameras for instance), here the attention shifts more towards the carved bibles as a split beam, refracted into South Africa’s eleven official languages. It’s a subtle and incredibly sharp detail in Botha’s consideration of the relevance of Christianity in a post-apartheid South Africa, and one that deserves to be in the neon pink spotlight for a bit.

One work which feels like the remnants of an ‘intrinsic field subtraction’ experiment within this context is the profoundly unsettling commune onomatopoeia, Botha’s 2003 work most notable for travelling as part of Simon Njami’s ‘Africa Remix’ exhibition back in the day. It’s always been an elusive and tricky critter to pin down, but in ‘Heliostat’, the displacement of the floating mid twentieth century middle class Afrikaans furniture vehemently comes across. The installation feels like an entity whose core has collapsed and is threatening to buckle in on itself at any moment. The drip, drip, drip of the water above the table a harbinger of this imminent implosion.

Wim Botha, commune onomatopoeia, 2003.

Wood, stonecast, etchings, stained glass windows. Installation view: Norval Foundation, 2018

That dripping sound gets under your skin and follows you around the first half of the exhibition, particularly in the neighbouring space housing Mieliepap Pietà. Faced with this juxtaposition, I couldn’t help but think of the incident in 2012, when Indian rationalist Sanal Edamaruku was forced to flee to Finland after proving out that the tears trickling down a statue of Jesus Christ in Mumbai were not miraculous holy water, but instead sewerage water seeping through the wall on account of faulty plumbing. There’s a wonderful curatorial subtext here of religious belief gone awry, divorced from its intrinsic field.

While the first half of ‘Heliostat’ may come across as unsettling, this impression is more than offset by the utterly gorgeous spectacle to be beheld in Gallery 8. If there’s a single word to describe this installation (the one housing the afore-mentioned walnut doppelgänger of Dr Manhattan), that word is ‘definitive’. It’s such a thorough encapsulation of everything that Wim Botha has been working towards in recent years that it’s hard to imagine a better summation of his oeuvre. And indeed, if the artist’s work has come across as treading water a bit in recent years, it’s clearly only because he’s been banging up against a dichroic glass ceiling, with regards to available space.

Having been given the opportunity to go wild here, the end result is sublime in every sense of the term and verges on a religious experience; especially when viewed in the evening as the light refracted from the dichroic glass shifts from a cool subtle ambience to fiery cadmium orange. If a space devoid of intrinsic field is uncanny and unnerving (as per commune onomatopoeia), the realm where this field is allowed to flourish is a space of rampant joy and wonder. Needless to say, Norval Foundation’s Gallery 8 is certainly one of the most exciting exhibition spaces in Cape Town at the moment, and Botha’s Studies for the Garden of Earthly Delights is going to be a tough act to follow.