Open24hrs, Cape Town

13.02 – 27.04.2019

It’s difficult – or maybe just pointless – to write about any particular Ed Young work or show as separate from his personal canon. This canon has in turn become pretty much inseparable from Young’s persona: art’s (aging) bad boy; predictably edgy and offensive, always already making fun of himself before anyone else gets the chance to. Young’s oeuvre has, for a long time, been anchored firmly in the realm of snappy one-liners and sarcastic social critique, often relying on the provincialism of Cape Town’s art scene to get the joke across. The tone of this type of satire has, in relation to the shifting current of contemporary art, fallen out of popularity (and perhaps also relevance). I think that Young acknowledges this, and has in the past expressed a level of surprise and confusion about how he’s managed to remain someone within the Cape Town art scene, even if that someone is a (willing) patsy for the rest of us – annoyed at the same art scene’s continuing unequal allocation of resources towards white male artists and its insistence on the importance of their work.

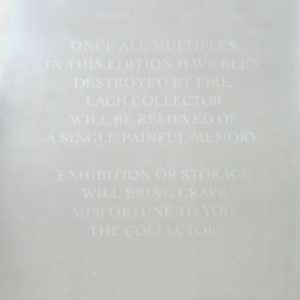

Young’s installation HERO, currently showing at Open24hrs (an unconventional and very new exhibition space) is ostensibly not much of a departure from his previous work. It consists of a life-sized, highly realistic sculpture of Young styled as a slightly worse-for-wear version of Superman – his gravity defying, metres-long cape extending behind him – and a text piece / poster in the recognisable Ed-Young-bold-condensed-sans-serif, consisting of the phrase “call your mother”. The visual language is in keeping with Young’s style, but the tone and energy of the text work in particular seems to have shifted away, slightly, from predictable polemics and towards something more diffident and gentle.

This is particularly clear in the phrase “call your mother”, which recalls Young’s earlier repeated use of the popular comeback “your mom”, most notably worn as a slogan t-shirt by Buttercup, Young’s bird-flipping teddy bear from his Bears series (2015-16). In this case, however, the grammar is different: there’s an action to the object. Unlike the implied action in “your mom” – which could be anything, but it’s probably rude – here the action can be interpreted as tender: an action of checking in, communicating, asking your mother how she’s been doing.

The central sculpture in ‘HERO’ is also a throwback to Young’s 2004 video work It’s Not Easy, a supercut of clips from Richard Lester’s Superman III (1983) in which the titular hero, played by Christopher Reeve, is shown in various states of emotional distress and physical vulnerability. The video begins with a shot of Superman in an idyllic setting, looking at Strelitzia flowers – a funny, incidental nod to South Africa – set to the soundtrack of Five for Fighting’s 2000 soft-rock ballad Superman (It’s not Easy). As the video progresses the clips become more violent, with the lyrics “I’m only a man in a silly red sheet” cut to footage of Superman drunk at a bar using his powers to smash liquor bottles (in the full film Superman – the persona – goes on to battle with a mental projection of his “real” self, Clark Kent). As the ballad reaches its sentimental crescendo, the video cuts quickly between shots of the superhero being flung into buildings and on to the windshields of cars, flinching in front of an explosion, and crashing through the heavily branded side of a Marlboro cigarette truck.

The juxtaposition of Five for Fighting’s embarrassingly serious lament about the difficulties of “being me” with this montage of Superman experiencing a series of beatdowns is simultaneously a totally ridiculous parody and a fairly sensitive investigation of heroic masculinity and the problems that come with attempting to perform it. Like It’s Not Easy, ‘HERO’ seems to toe the line between gleeful self-flagellation and vaguely bewildered self-pity. Young’s sculptural doppelgänger holds a battered box of Marlboro reds in his one hand, a lighter in the other, and an unlit cigarette in his mouth. He is wearing the costume of the hero, but doesn’t look as though he’s able – or particularly eager – to apprehend any villains. Despite his carefully cultivated aura of invulnerability this hero is tired, he’s despondent, he’s aged beyond his years and he’s down to his last smoke.

HERO’s central sculpture was conceptualised over five years ago but until recently was never afforded the space or funding to be finished until Open24hrs, which is technically a private collection, offered Young the opportunity to exhibit. This model, which is based on individual commissions as opposed to sales-based speculation, is attractive in that it allows artists to produce work relatively free of the constraints of the market. The space itself is located in the lobby of an office building on Harrington street, which means that a fairly diverse crowd – including people who work in the building, passers by, and deliberate visitors – is exposed to each show.Although ‘HERO’ is only the second acquisition that Open24hrs has exhibited, it has generated a level of online hype (and probably accrued more value) uncommon in conventional gallery exhibitions. This can be attributed partly to the open nature of the space and its increased traffic, but also in a large way to the spectacle of the work itself – the sculpture’s hyperrealism, its impressive construction and its tongue-in-cheek reference to the well-known superhero providing a perfect backdrop for instagram photo-ops and general self-generating online virality. Because Superman is a pinup; a piece of pop-cultural symbolism, his representation is transferrable and can be transplanted into any number of different narrative universes. The hero (as a genre, an object, an image) is already a loaded signifier which, in this context, Young has simply tacked his own persona on to. Even if spectators have never met Ed Young or seen his work, they’re presented with this unbothered, rough-looking action figure for adults – a subversion of the pinup; they are still able to get the joke.

The creation of a personal brand or canon can be figured as the production of an heroic image, or fetish, that goes on to reproduce itself, which is also often the problem: the actual person tends to outgrow it. HERO seems symptomatic of this, but as much as the subtext of the work may be to abscond from the public persona and phone home, the work itself – in its materiality and its spectacle – continues to feed into its own mythology, undercutting any potential for earnest self-critique on Young’s part. In a way, this is a condition of the canon that Young has constructed. The joke becomes cyclical and self-referential, it’s impossible to deconstruct without descending deeper into its own machinery. The apparent lack of frank engagement with anything outside of itself is also part of the issue. Yes, it is a joke: Young is poking fun at himself and the superhero genre in general; he’s poking fun at his own cult of personality, and perhaps he’s indirectly critiquing the audience’s desire for instagrammable spectacle by having something extraordinarily spectacular fabricated. But it’s a very expensive joke – one that crumples under the weight of its own polish and execution.