Johannesburg Art Gallery, or JAG as it is affectionately known, seems constantly the target of some or other misfortune. The grand, Classical building, which is perpetually under construction, holds the largest collection of fine art in the country. While the gallery struggles under municipal jurisdiction, the lack of communication with the public with regards to these problems creates more isolation and can only prevent public/ private interventions. Last year, JAG celebrated the centenary of the Luytens building through the release of a new book titled “Constructure: 100 years of the JAG building and its Contribution of Space and Meaning” and a series of three limited edition commemorative sterling silver medallions. This traditional museum-like celebratory convention is an aspect of JAG’s identity, however there is a contemporary layer to the gallery, which speaks to the building’s everyday relevance. The gallery’s recent addition of an Educational Officer onto the staff as well as the recent opening of contemporary exhibitions, promotes the gallery’s interest in the now, the current, while still acknowledging the past.

Tara Weber a graduate of Michaelis’ Curatorship Honours, and a passionate museum aficionado, has worked as the gallery’s registrar and co-curator for 2 years. Weber recently organized and curated ‘Free Me From My Happiness’ an exhibition of three young, very young, South African photographers all under the age of 22; Sibusiso Bheka, Tshepiso Mazibuko and Lindokuhle Sobekwa. The opening stood as a testament to the hunger of Joburg for contemporary photography; a diverse crowd of over 200 people attended.

The show was first exhibited in Belgium at the Ghent International Photography Festival in 2015. As proponents of the Of Soul and Joy project, funded by the Rubis Mécénat Cultural Fund, Bheka, Mazibuko and Sobekwa have been given the opportunity to learn these skills and exhibit internationally. While these three artists might appear to have much in common (most obviously their use of a documentary style and the fact that the photographs were all shot in Thokoza, a township in the south of Johannesburg ), but after spending some time in the space the works and artists emerge as individuals embracing their own idiosyncrasies.

Sibusiso Bheka’s At Night They Walk With Me, the only work in colour, captures an almost surreal dream world with a formal eye, ‘Magical Realism’ as Sean O’ Toole has described it. Instigated by the idea of ghosts, after being told as a child that “…if you play at night you are playing with ghosts”, Bheka elicits the atmosphere of a place rather than the people who occupy it. The familiar stillness of his works, almost suspended in my own memory somewhere, have the confidence of a seasoned photographer.

Tshepiso Mazibuko’s Encounters, black and white works, in contrast seem to focus on the social. Interior spaces, private moments and the sacred, lived spaces of Thokoza captured in a documentary-style. Mazibuko had ambitions of becoming a journalist, a dream now fulfilled visually. Using her camera as a means of connection, Mazibuko develops relationships with her subjects, sometimes awkward, with an air of benevolent curiosity.

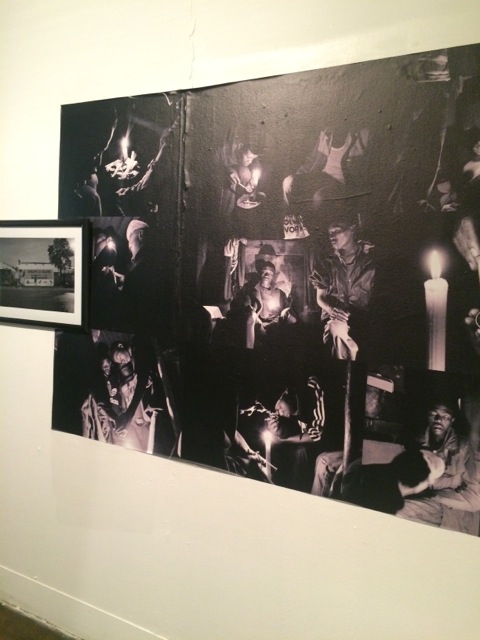

Lindokuhle Sobekwa’s Nyaope. Everything You Give Me My Boss, Will Do, as if documenting an entirely different world from the two artists before him, reveals another side of Thokoza that of candle lit Nyaope binges. An unsettling glimpse of clandestine spaces- raw, personal, and intimate.

As part of JAG’s new exhibition strategy, the inclusion of younger, less established (however rapidly establishing) artists provides a platform for large-scale installations, a certain agency in the curation process and the dreaded but necessary ‘exposure’ without the pressure of having to deal with the art market directly. This show, which could also be labeled a labour of love by the exhibition team, involved the creative re-use, and renovation of existing frames from the JAG storeroom, the painstaking design and folding of hundreds of zines/ take-away information on each artist as well as the idea of creating business cards for the artists instead of the traditional postcard invitations. JAG’s team seem to skirt the fine line between philanthropy and exigency, making the best of what they have and putting in the extra hours encouraged by the mutual benefit for both the artists and the perception of the gallery.

JAG has recently acquired a new educational officer, Colin Groenewald, an ambitious young man with big visions for the gallery. As education officer, Groenewald aims to draw students in, children but also adults, to change the perception of the gallery, to create an inclusive, interactive space. Working predominantly with local communities, the gallery is positioned not only as an art institution but also as a space to do homework and other educational workshops. One of Groenwald’s visions includes the renovation of JAG’s bus to ‘bring the museum to the people’.

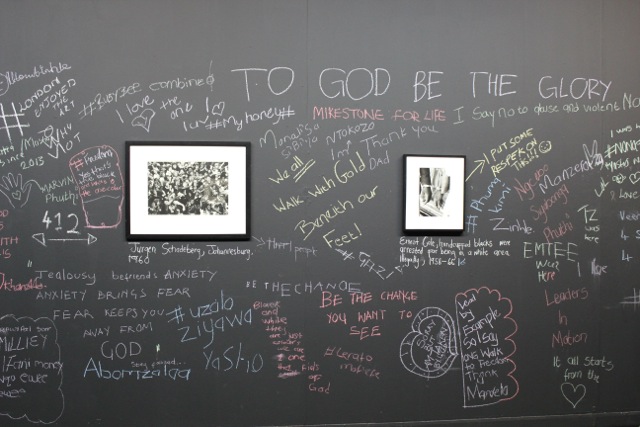

JAG’s Workshop Room (previous Project Space) is currently activated as part of Youth Day educational workshops. The room, painted in black chalkboard paint, is a space for students to see historical photographs from 16 June 1976, but the space is also theirs, an interactive space where students are encouraged to write their own opinions and ideas on the walls of the gallery. The Workshop Room is also a great collaborative tool, a means to allow students access to established artists in an informal way. On Youth Day the film The People versus the Rainbow Nation, directed by Lebogang Rasethaba about the #feesmustfall movement will be screened in the space for a large group of students, which should spark debate around the political history of education and the current fight for free education.

While JAG negotiates the complexities faced by all museum spaces in South Africa, it is further complicated by its geographical location. Often confused as a police station by passers by and locals of the area (the entrance has been co-opted by Metro Police who seem to have their daily exercises, training and debriefings there), the gallery can appear invisible to contemporary society. However, these apparent small steps taken to engage the children in the area and to draw in the youth to admire young artists just like them, could be seen as giant steps towards rethinking the purpose of the museum in this country.