blank projects

29.07 - 19.08.2023

The opening of Fullhouse at blank projects felt strangely momentous. Like a transitional moment for the small, nuclear art scene in Cape Town. A blip on the radar in the grander scheme of things, perhaps, but even small, nuclear art scenes deserve to get the art historical treatment.

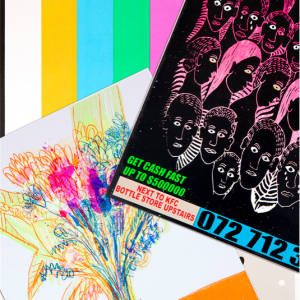

On paper, it looked like a textbook winter show. The team of curators from Under Projects and FEDE Arthouse asked a bunch of artists in their orbit to submit work. Some of them responded and the show was a rough assembly of the work the curators received. The bulk of the exhibition was held in a makeshift antechamber and stacked haphazardly on diagonal shelves. From this crowded pantry, a handful of objects were taken, on a rotating weekly basis, into an adjacent room and arranged more thoughtfully there.

The offhand effortlessness of the show worked a kind of magic that I could not wrap my head around at first. Under Projects has been honing this cluttered curatorial style for a while now, but most of their group shows are unashamedly janky. Fullhouse felt very different. Everything looked good — crisp, even — and I was shocked to find out that the curators had followed a similar vetting process (or lack thereof) this time around. Upon a second visit, to view another iteration, it was clearer to me that many of the pieces would not have made much of an impression on their own. However, by some alchemy, they seemed to shine in the context of Fullhouse.

Working in a more flattering space certainly helped, but what makes the show stand out, I think, is a very precise art historical confluence. Where the exhibition lands within a larger narrative of the relationship between art and politics in South Africa, and the role of the curator within that relationship, is worth noting in this case. The status of politics in relation to art is easily taken for granted around here, though it is continually negotiated and historically contingent. For better or worse, Fullhouse has brought changing attitudes towards the question of art and politics in South Africa to a head.

First, some context. There is a long history of political commitment in South African art that is, for the current generation, epitomised by the anti-apartheid truth tellers associated with struggle photography, The Drum generation, protest theatre, et al. After 1994, political commitment was mainly expressed through critical engagement with representation, which had its moment around the time of the 2nd Johannesburg Biennale and the infamous Grey Areas publication. Discontent simmered within this register until everything changed with the Marikana Massacre in 2012 and the subsequent #feesmustfall (FMF) movement. The latter, in particular, breathed new political life into the art ecosystem.

The impact of FMF on contemporary art discourse in South Africa was significant, though it harkened back to many of the unresolved talking points raised in the 1990s. Yet there was a renewed urgency brought on by the student protests that had been unavailable in the decades prior. What followed was a kind of golden age for political rigour in South African art and criticism. Artists started identifying as “cultural workers,” a term borrowed from the Medu Art Ensemble to describe the integration of artistic and social practice. The iQhiya collective emerged as the commanding voice of the FMF generation in the field of contemporary art. Bronwyn Katz, Thuli Gamedze and Lungiswa Gqunta, along with the rest of their star-studded cohort, exemplified what political commitment could look like after the end of rainbow nationalism.

None of this was happening in a vacuum. The mood reflected global trends that were being disseminated online and recalcitrant South African contradictions that artists, scholars and activists had been wrestling with for ages. But what mattered, once again, was the way it coincided with a particular historical moment that felt unprecedented. It felt as if artists had real political agency, even when they were expressing insurmountable pessimism. Young practitioners, especially those coming out of the universities, thought deeply about the political implications of their work. It was as if the art world was subject to a new political superego.

While the politicised atmosphere that followed FMF was incredibly fertile for criticism, it did not, or could not, always encourage artistic irreverence. The new political superego, even when it was entirely imaginary, seemed to probe artists’ work for inconsistencies, or ghettoise them based on their marginal identities. It assumed the form of the internal saboteur that inhibits and conforms. Increasingly, I found myself having hushed conversations, mostly with other white guys, about how the state of affairs had hamstrung the arts and letters in South Africa. Most of these discussions were wildly overstated, but they were trying to articulate something precise about the often fraught relationship between art and politics.

In stark contrast to the political rigour that has been central to curatorial practice over the last decade or so, the curators of Fullhouse prefer not to overthink it. Whether or not it was intended to be, the exhibition feels like an antidote to curatorial standards in South Africa. Yet their irreverence, as such, would not be worth writing about if the show was any less successful. Fullhouse makes a substantive case for the legitimacy of curatorial irreverence beyond the project space. Their approach is far from unprecedented — the influence of Ed Young and Avant Car Guard, for example, is all over this sensibility — but the way Fullhouse circles back to that irreverence feels stark in the wake of FMF. It is loaded with a very different historical meaning.

There is an air of resignation about this attitude now. It smacks of COVID era atomisation and political ennui. Even the political gestures that made it into the show felt subsumed within the clutter of artworks. There were a couple of Vusumzi Nkomo pieces that circled the concerns of afropessimism and, while striking in their own right, their edges were softened in relation to the whole. Sitting alongside Yonela Makoba’s tapestry of stained tea bags, aptly titled Potential no more, the prevailing tone was one of political disappointment. And what could be more true for this generation of artists? The fact that contemporary art has become all but defanged is disheartening on the one hand, but a more optimistic reading might be that South African art needs to transition into a new mode, in order to potentially come at politics in a different way.

Something about looking at a roomful of unbound ingenuity feels politically meaningful as well. It is disarming to find a group of artists so enveloped in their practices that they feel no need to produce anything of consequence. I spent ages pouring over Jared Ginsberg’s two second loop of a bottle spinning inside an overflowing drain pipe, for example. A minor gesture from a major artist, but it perfectly occupied its corner of shelf. Minor works abounded and they were imbued with an off-beat sublimity. Nazeer Jappie’s home video of a low-key tap routine set the easy tone. There was some kind of serpentine tangle of green rubber looming on one of the top shelves, while a Githan Coopoo pot in front of me promised “GOOD FORTUNE INSIDE.” I had to restrain myself from fingering through the stack of Kamyar Bineshtarigh paintings, although I am sure no one would have minded. The stakes of the room were low, but I did not want to disturb the equilibrium.

Even the curated space was pretty much empty of meaningful content, but the free play of forms guided my attention around the room. Ben Orkin’s ceramic screw spiralled upwards, while a line of Inga Somdyala’s sandbags veered off into one corner, announcing Tyra Naidoo’s smears of leftover foodstuff across the wall above. Once more, it was the minor work that stood out: Callan Grecia’s pale painting of some guy wearing a sweater that says “Colorado” really moved me, for some reason. At the entrance, a timelapse video of the curators mixing and remixing the exhibition called attention to their nimble curatorial style.

My second visit to the exhibition was more moody than momentous. The gallery was eerily quiet compared to the opening, and all the videos were off because of loadshedding. The reshuffled curation suited the somber tone as well. Mboma’s portrait of a sickly aristocrat drew my attention first. The ominous speck of blood on his collar rhymed with the deep red circle at the centre of Nkomo’s Sound Mirror #3: Amaqaba in Manchester. Mankebe Seakgoe’s cloud of red wire turned quietly overhead, and Micha Serraf’s woolen landscape hung low, close to the ground. The atmosphere matched Bella Knemeyer’s In the lee: the artworks felt like faint imprints on a textured surface, in blue. It caught me off guard, like a plot twist, but I appreciate that I got to see two very different sides to the exhibition. It mirrored the dichotomy between fresh and empty that I have tried to unpack in this piece.

Fullhouse might be an isolated incident and it may not lead anywhere, but my sense is that a certain curatorial attitude that has been nascent for a while assumed form in this exhibition. There might be something regrettable about the turn to irreverence, but it is my hope that the loose-limbed creativity that a show like Fullhouse inspires might free up some kind of energy. Let’s see where it takes us.